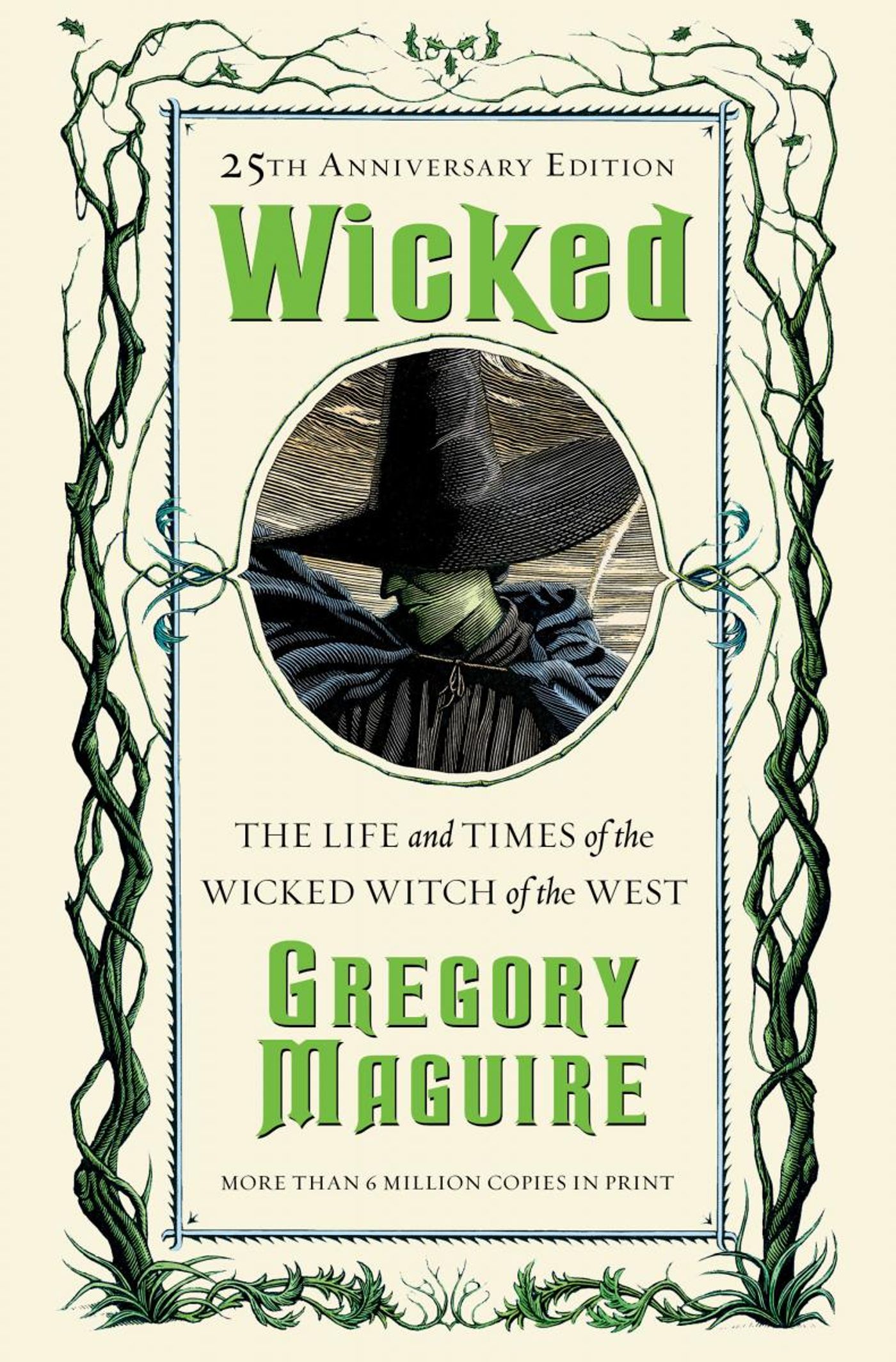

Interview: Gregory Maguire Talks 25th Anniversary Edition of the WICKED Novel, Dream Casts the WICKED Movie and More

The 25th anniversary edition of WICKED will be published on October 13th.

Wicked has been leaving its mark on pop culture for 25 years, inspiring millions as people all around the world continue to discover and rediscover this story that is both classic, and unmatched in its originality and impact. The novel, Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West by Gregory Maguire was first published in 1995, and was further cemented into the fabric of our history when it was made into a global phenomenon of a musical in 2003.

More than two decades after the original publication of the novel, a 25th anniversary edition is being released by HarperCollins on October 13th.

You can pre-order the 25th anniversary edition of Wicked HERE!

We spoke with author Gregory Maguire about the impact of Wicked, why the themes in the book are more relevant now than ever, who he would want to star in the Wicked film, and more!

What can you tell us about the 25th anniversary edition of Wicked?

The main thing is that I have provided an extensive afterword to be included at the end of the novel, which is a consideration, I think, of my beliefs about the value of children's stories and how they carry, coded and coiled within them, material that not only is suitable for children when we first get it, but actually continues like radiation to give off useful nutrition for the whole of our adult lives.

What was your first experience with The Wizard of Oz? Was it the movie? Was it the book?

I am from a very bookish family. We were kind of like a librarian version of the Von Trapp family, we didn't sing together, we read together. So, for most stories, I knew the book version first, but for The Wizard of Oz it was a rare exception. The Wizard of Oz started to be broadcast annually on CBS I think it was, in the late 1950s when I was about five, and then was broadcast annually until the beginning of what I call "the video mesmorama", where you could get them 365 days a year at-will, on demand. So, because it was one of the few movies I saw in young childhood and I saw it repeatedly, it took on the kind of appeal of almost a bible story, it was like the nativity, it was like going to church at Christmas and Easter. There was Christmas, there was Easter, there was The Wizard of Oz.

Where did you first get the idea to write this sweeping backstory to the Wizard of Oz, and why did you decide to make the Wicked Witch of the West the heart of the story?

In a way, there are at least two beginnings to my decision to do it. There was the unconscious beginning and the conscious. The unconscious beginning was back in childhood, because after the film was shown, I would gather together my brothers and sisters and neighborhood kids who didn't have a scrap of imagination among them, and I would say, "Okay gang, listen up, here's what we're going to do today!" And I would arrange a kind of troupe of improv players to act out The Wizard of Oz after it showed.

In a way, there are at least two beginnings to my decision to do it. There was the unconscious beginning and the conscious. The unconscious beginning was back in childhood, because after the film was shown, I would gather together my brothers and sisters and neighborhood kids who didn't have a scrap of imagination among them, and I would say, "Okay gang, listen up, here's what we're going to do today!" And I would arrange a kind of troupe of improv players to act out The Wizard of Oz after it showed.

But, fast forward another, maybe, twenty five years, at the beginning of the Gulf War in 1991. At the time, there was so much worry about Saddam Hussein, and I remember seeing a newspaper article that said, 'Saddam Hussein, the next Hitler?' and when I saw the word Hitler, my blood began to run cold because there can hardly be a word that is scarier in the English language, if you're a person who tends toward dread, than Hitler. And even I, who am fairly pacifist, if not very pacifist, found myself thinking, "Well, who among us wouldn't have picked up arms against Hitler if we could have known the damage he was going to do to the world?" I began from there to think about how we seem to need to use words of degradation in order to dehumanize our enemies, in order to be able to pick up sticks and stones and go to battle against them. We have somehow to believe that they are less human than we are in order to get the courage to kill them. I began to think then, really, "What does make somebody wicked? What is evil, and how do we use it socially and culturally? How do we use the concept as a legitimization of our inclination toward greed and self-involvement and self-rationalization?"

I began to cast about for a way to write about evil, and up to that point I had only written books for children. So, I remembered the rubrics that say, 'write about what you know' and I think, "What do I know, Catholic church music? The only other thing I know is children's books, and there's no evil in children's books by dint of the fact that they're for children. And then I had my one great revelation of my life. The scales fell from my eyes as they did for Saint Paul on the road to Damascus and I saw that there are villains in children's books, and I thought, "Well, of course there are, and of course they're stock villains, because otherwise we couldn't hate them," and, "Who's the worst of them?" And coming down from the sky on a cloud, approaching me in a heavenly vision, was not the Virgin Mary for whom I've been waiting for most of my adult life, but the Wicked Witch of the West, saying, "I'll get you and you're little dog!" And I thought, "Jesus, Mary and Joseph I've had a religious vision, and it's Elphaba."

Let's talk about the musical! Wicked is one of the most successful shows in Broadway history, what were your thoughts when you first found out someone wanted to make it into a musical?

I will say that all the time, writing the novel, I thought to myself, "This is a really good idea. If I can pull it off even to a minimum level-I mean I would like it to be a great novel-but even if I can pull it off to a minimum level of success, it's such a good idea that it will likely get some movie or TV interest." I even cast a film in my head as a way to help me visualize it. I had the young Antonio Banderas in my mind as Fiyero, when he was about 25. Elphaba was played in my mind by the young k.d. lang, who, a). she could sing, and b). she had a very pointed and spiky kind of individual beauty that was really beautiful, but was not like anybody else. And Angela Lansbury played Madame Morrible in my mind. Melanie Griffith played Galinda.

So, when the book was published it almost immediately got optioned by Demi Moore and a production company she ran, which had a relationship with Universal, and there was a chance for it to be a big budget film almost right away, but the film never quite crystallized. And then Stephen Schwartz, the magnificent Stephen Schwartz was out snorkeling, as I understand the story, with Holly Near. Holly Near and Stephen were friends and they were on holiday together or had at least run into each other in Hawaii someplace, and Stephen said, "What are you reading these days?" And she told him, "I'm reading Wicked, this book about the Wicked Witch of the West" and Stephen said, "Sounds like my return to Broadway,"

We met in Connecticut, we went for a walk, and he told me some of the ideas he had regarding the play. He told me that the thing about my novel is that it was built on a 19th century belief in the moral universe, and that the characters had great, deep, pre-Freudian instincts and emotions that were pre-modern and would not do very well on the big screen, but they would do very well when sung. And he went on and he said, "Gregory, I'm so convinced that you're going to see the correctness of my vision, that' I've already conceived the first song. It's going to be called 'No One Mourns the Wicked,'" And with the phrase, 'No One Mourns the Wicked' he said to me without quite saying it, "I catch the nub of why you wrote this book. I understand it." And, at that moment, though he didn't find out for about a year, until my agent and lawyers were through with negotiation, he had finished selling the job to me. I came home and I said to myself, "I'm going to let this happen, I don't care about the money. This is far more in line with why I wrote the book than the movie scripts I've read so far about Wicked,"

What is it like for you knowing that your work is a part of something so huge, that has had this massive effect on not only theater history, but on all of popular culture?

I think that if I hadn't begun adopting my children at just about the time that Wicked was beginning to be developed for Broadway, it might have made me unbearable with pride and with self-admiration. But the truth is, if you've got little kids screaming for Cheerios, it doesn't matter what Broadway websites say about you, you've got to get the damn Cheerios on the table! I have been aware of it as a kind of life change for me, it certainly has made my life less fiscally perilous, there's no doubt about that. But, in terms of it changing who I am as a writer or as a citizen or as a parent or as a creative person, it has perhaps had less effect than you might think by virtue of the fact that my parental duties came first, especially at that point.

When the Broadway cast recording was first coming out in roughly December of 2003, there was a recording reveal party in the lobby of the Gershwin, and I was invited to come down from Boston to sit in the line with other cast members and sign albums as they were passed along. I kept watching Idina Menzel at the other end of the table. And at roughly every seven or eight persons, she would get up from her folding chair and lean across the table and give somebody a hug. And I got interested, I went, "What's going on over there?" And I eavesdropped on, the next time it happened, there was a young woman... and she came up and she leaned over to Idina and she said, "I need to tell you, I have been living in this country for eight years, and this Elphaba is the first time I have ever seen myself in this country."

And I thought, "I have heard from so many people that Elphaba is them and they are Elphaba," that I am staggered with gratitude that I was able to key into some combination of personality that was both fragile and strong at the same time, and that speaks to all of us... I was able to use what I had and give something to somebody else. That's all we ever hope to do in life, isn't it? It legitimizes our time on this earth a little bit. And so, I've legitimized mine, and I have given people comfort, at least a few, a least a little, and that's enough for me.

The themes of your book, why do you think- or do you think- that they are more relevant now than ever?

When it came out I was afraid it would be found very retro and a little obvious, and then when I did ink the contracts to let the theater people begin to go to work on a play, 9/11 happened. I thought, as Alan Bennett, the English playwright would say, 'That puts paid to this project', because who is going to want to look at a play now that questions how we legitimize our aggression against our enemies, when we've just been attacked by Bin Laden? I thought that would really quash the project forever, but in fact, the opposite happened. The moral question that the play and the book ask became more urgent since the day that it was published in 1995. The world has become more dangerous and despotism has become more apparent, not just in the Middle East, but in Europe, and our own Western Hemisphere as well. And so, it shocks me and saddens me that I think the story is more urgent now than it was twenty-five years ago, but I think it is.

What is your favorite scene in the book?

That's a really good question! It's funny because the scene that the play memorializes as the song Popular, where Elphaba and Galinda both put down their guard for the first time and become willing to consider that each other as human, was a scene that I loved writing because it gave me a chance to highlight Elphaba's intellectual side. Up to that point, Elphaba had only been weird and dangerous and green, but here, in college, it was the first time I was able to write a scene in which she could talk about how she thought. She was thinking about the nature of evil, and she was thinking about whether evil exists, in her bedroom, and Galinda comes in and wants to try on a hat. And in the interest of starting to make fun of Elphaba by giving her a too-weird hat that she imagines she is going to laugh at with her friends and say how Elphaba couldn't even see that she was being made fun of, she accidentally notices that Elphaba is beautiful, and she realizes she has been being talked to like a real person and not just a bubble head for the first time. So, the moment that their friendship begins in the book was deeply gratifying to me to write because it allowed me to explore both of those women's strengths and vulnerabilities.

Before the pandemic, there was a lot of talk about the Wicked movie. If you could dream cast the movie, do you have an idea of who you would want to do it now?

I have had a dream cast that has to keep changing every couple of years because the time goes on and people get too old for the roles. I know I've heard Kristin Chenoweth say, "They better hurry up and make this movie, Wicked, or I'm going to have to play Madame Morrible!" And indeed, she and Idina Menzel are too old for the roles of ingenues at this point. Their voices are just as good, if not better, than sixteen years ago, but they are too womanly, they're not girlish enough.

I sure was thrilled with Ariana Grande singing 'The Wizard and I' at that fifteenth-anniversary TV special. She just really knocked it out of the park, I thought she was great. For the characters who are a little bit older, I mean, Angela Lansbury is still around, it's not too late for her to be Madame Morrible! I loved Miriam Margolyes when she played Madame Morrible, and I loved Carol Kane when she played Madame Morrible. I used to wonder about whether they could even get somebody like Meryl Streep to play Madame Morrible, and I would love to see that. There was a time a few years back when I thought Darren Criss might be a good Fiyero, partly because he's part Filipino, and in fact, when I wrote Fiyero, I had Southeast Asians as part of my inspiration for what he looked like. But, he too, I mean, people get older. Now that Norbert Leo Butz is an older person, maybe he'd be a good Wizard!

Is there anything the musical does that you wish you had thought of?

People have sometimes said to me, "The musical changed your book and they made much more of a romantic competition between Elphaba and Galinda over Fiyero than your book did, and furthermore x, and furthermore y." I'm very happy with the way Winnie Holzman and Stephen Schwartz chose to tell the story. It made efficient, economic, and narrative sense for them to make the story choices that they chose to do, and I applaud it completely. The play is a little less subtle than the novel in some ways. And I wanted the novel to be more ambiguous because that's the nature of how I was trying to tell my story.

To be ambiguous was my intent in the novel, partly because I wanted to pose the question, "How do we know what evil is and how do we know when we see it?" I wanted to pose the question, but I did not want to answer it, I wanted that answer to have to be the job of the reader. And so, to follow that along, I also pose lots of possibilities. What was it about Elphaba and the fact that at the beginning they couldn't determine her gender? What was it about Elphaba and Galinda and their strong association for which neither of them really had the words or the experience to name? Why did Glinda turn away from Elphaba in the Emerald City when the notion of Fiyero came up? Again, there was an embedded suggestion on my part that, even though it doesn't seem to come up in the book, that Glinda did hold a candle for Fiyero and always had, and I just put the tiniest little suggestion there in one or two scenes. I wanted people to think, "Oh, what is that about?" And not be able to think, "I'll find out on page 412. No, I just have to think about it." Because all human behavior is mysterious and ambivalent, and it is our job to look at contradictory information and come to the best conclusions about it that we can. And I wanted the novel to seem, even though it was a fantasy, more like life than life itself.

Pre-order the 25th anniversary edition of wicked HERE!

*This interview has been edited and condensed.

Photo Credit: Andy Newman

Videos