Interview: Baritone Etienne Dupuis Brings His 'Je Ne Sais Quoi' to DON CARLOS at the Met

His favorite role is a surprise, as is his favorite singer

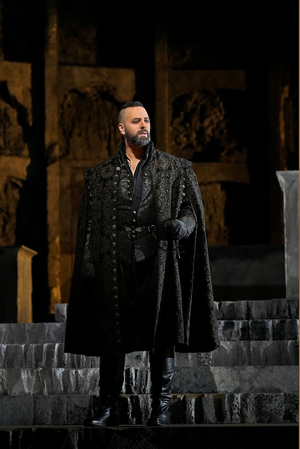

Can you imagine the Met--or any other major opera house--cutting the length of a new opera so commuters could make the last train? That's what baritone Etienne Dupuis told me about the world premiere in Paris (in French) of Verdi's DON CARLOS (1867). Dupuis is starring as Don Rodrigue, Marquis de Posa, at the Met these days, in the new David McVicar production of the Verdi opera.

Because of the cuts the composer made for the opening and afterwards--everyone seemed to think it was too long--and many other changes to the work done later, there are more "official" versions of DON CARLOS/DON CARLO (primarily based on the play by Friedrich von Schiller ["Don Karlos, Infant von Spanien" - "Don Carlos, Infante of Spain"]), than even the most ardent opera lover might think twice about sitting through.

The Paris-based Dupuis, who sang spectacularly as Posa in this new production at the Met, has sung many of the versions, in French (his native tongue) and Italian, with substantial changes in the music, including many of the ensembles.

Ken Howard/The Met

For example, there's a significant shift in the famed duet between him and Don Carlos, sung wonderfully here at the Met with tenor Matthew Polenzani (whose French he called "insanely good--especially his musicality"), as well as in the ending.

When I told him I thought there was something about his Posa that was "different," he said, modestly, that some of it was style, since French is his native tongue. (He was born in Montreal.)

"I think there are a few things that make me different from the other principals, part of which is my experience singing the role both in Italian and French [including the 4-act-version in Italian at Deutsche Oper Berlin and the 5-act-version in Italian at the Paris Opéra in 2019], which gives me a different understanding of it. I know the layers of the music from more than one angle," he explained. "Plus working with Yannick [Nezet-Seguin, the conductor, another native French-speaker]; we can make music together and understand one another without much to talk about."

Ken Howard/The Met

Then I brought up the matter of a homoerotic overtones in his relationship with Carlos in this production; he said that he's heard this argument many times, in many productions, and mostly poo-hoos it.

"To me, personally, I think that it's one of those rare cases when sex doesn't matter to a character, my character. First, much has to do with the concept of masculinity: The two men grew up together and were really close, with this incredible bond of trust--the only person each of them trusts. Isn't that a description of what a love relationship is? They trust each other in that way--like lovers would.

Photo: Ken Howard/The Met

"With Rodrigue, while he might have some emotions, he's really driven by the cause of saving Flanders: Who cares about sex when you have the lives of thousands of people in your hands?" he continues. "I've met people in my life like that--it's the cause that exists; nothing else matters. That's what Rodrigue is--'a dog with a bone.' That's it."

Rodrigue/Rodrigo is a prized role of his ("I'm glad I get to show what I can do dramatically, working with David McVicar on this role; it's very different from doing Mozart, for example, in the intensity and drama") but hardly the only one. He is looking forward to debuts in a couple of major Verdi roles--Rigoletto ("I know I can sing it, but I want people to say, 'Ah, that's what I want in a Rigoletto') and di Luna in TROVATORE--coming up, as well as John Adams' THE DEATH OF KLINGHOFFER. And he's had major successes with, among others, EUGENE ONEGIN, DON GIOVANNI and DEAD MAN WALKING (which he was scheduled to do at the Met when the Covid closedown occurred). But a favorite? Without hesitation, he answers: The title role in WERTHER.

Photo: Ken Howard/The Met

WERTHER? Not exactly the answer you'd expect from a baritone (who are generally relegated to the less interesting role of Albert). But, of course, baritones do sing it, though not often and there's not even an official version for that fach. During the 2020 Covid lockdown in France, he stepped into a concert staging at the Opera de Lyon, conducted by Daniele Rustioni, that was supposed to star baritone Simon Keenlyside, who suddenly pulled out--giving Dupuis an opportunity...but only three weeks to learn the role.

"I never expected it--and wasn't supposed to be free," he recalls, "but Covid being what it is, my thing was cancelled. Yes, it was the baritone version, but I switched a lot of things back to the tenor version--I have a higher voice than the baritone who created it--which let me reinstate some musical lines (I don't like when lines break). So I changed it as much as I could.

Ken Howard/The Met

"It was being recorded, which meant we had to work harder in less time than if we were doing a performance and it was quite tiring," he says. "My dream is to sing it the proper way and, probably reinstate more of the tenor stuff--there's much more I know I could do."

But would conductors let him make those changes? "Hopefully, it would be a collaboration. The orchestration doesn't change and if I'm not doing the high B (the tenor usually goes for the high note), the orchestra can't be so heavy and that's what they're used to, out of instinct. The baritone just needs a little help," he explains.

"I've even thought we should contact the Massenet Foundation (L'Association Massenet Internationale) and ask for an official version. Supposedly, all that happened when the opera was first done like this was that they couldn't find a tenor and when asked about a baritone, Massenet said, 'Sing it, it's fine,'" Dupuis says, laughing. "Of course, I've heard the Foundation is really against making a version official. But they should bless one--one that every theatre can do without feeling bad."

What was it like to learn it? "Ask my wife," he laughs. (That's soprano Nicole Car, a frequent collaborator of his and mother of his five-year-old son.) "She was getting fed up with it. I would go around in the street, walking my dog, listening to it on my headphones. It was all I wanted to hear--not only my bits but the whole thing. It was like falling in love with an opera for the first time again. It was like that with PELLEAS (which he sang at the Paris Opera); after the first time you perform it; you know it from the inside and you think of it in a deeper way, you realize how genius it is.

"WERTHER is like DON CARLOS to me--it's not a love story. I love how he's not entirely right in his head. It's so much more interesting to play than 'yes, he's in love and it doesn't work out.'"

Dupuis has another surprise for me, when I ask him about singers he admires. Number one: Jacques Brel, the Belgian singer-songwriter, who's known for his thoughtful, theatrical songs. ("You feel like you're watching a movie when he performs, because the songs come to life. It's important to have true communication when you do a job like ours.")

And, then, of course, there's Callas, a less unanticipated choice. "There's a story about her recording an aria from SONNAMBULA. When she finished, she was thrilled and said, 'That's perfection, the best I've ever done.' Then she went to the booth to listen and the technician's reaction was somewhat muted. She listens to the take and, from the first bar, she knew that she had to do it again--because she found it perfect vocally, but lacking in character: She had sung it, but not lived it.

"I love that story because she didn't care about how splendid she seemed--but whether she sounded like she knew she what she was singing about," he concludes. "For us, at the end, it is not 'that was great' or 'that was really impressive.' It's that what you do needs to leave a mark."

There are two remaining performances of the French DON CARLOS at the Met this season, on Tuesday evening and the Saturday matinee, which will be broadcast live to theatres around the world as part of the company's 'Live in HD' series. (Next year, they will do the Italian DON CARLO.) For more information, see the Met's website.

Comments

Videos