Reviewed by Barry Lenny, Sunday 4th March 2018.

Reviewed by Barry Lenny, Sunday 4th March 2018.

Thyestes, the original tragedy, a fabula crepidata (Roman tragedy with Greek subject), was written by Seneca the Younger (Lucius Annaeus Seneca) around 62 AD and tells of the rivalry between two brothers, Atreus and Thyestes, over who is to rule the city of Mycenae.

The Hayloft Project: Thomas Henning,

Chris Ryan,

Simon Stone, and Mark Winter, wrote this script, drawing on Seneca's play, and it is directed by

Simon Stone who, with Thomas Henning, and

Toby Schmitz, also performs in the work.

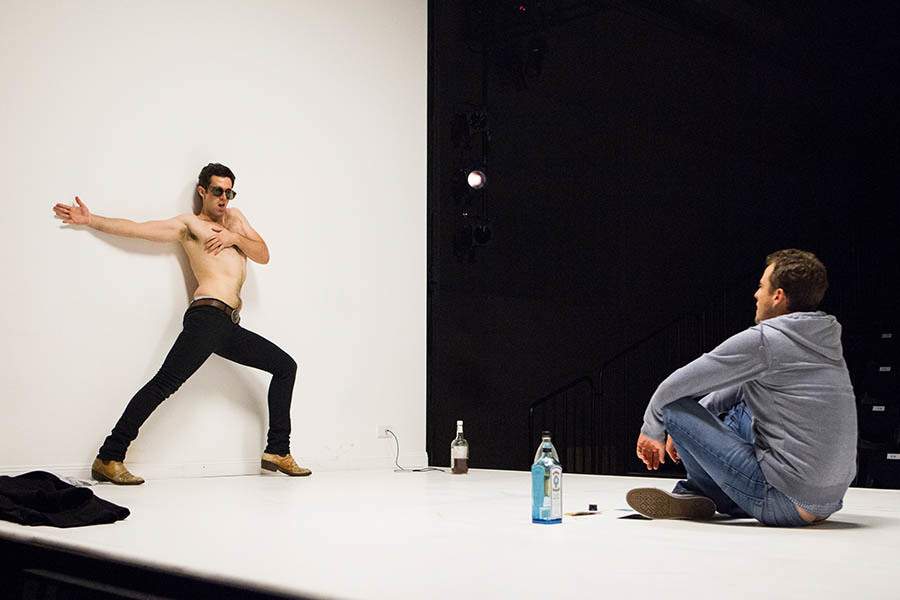

It is brought up to date and opens on three men, drinking red wine in copious quantities, one with his attention given to his mobile telephone, the others apparently talking nonsense. There is a great deal of comedy in the first scene, until its conclusion, when we remember that we had already been informed, by means of a screen announcing the scene number and synopsis, of what was to happen. We pay more attention to this screen between scene changes, after this.

This opening scene ends with Atreus and Thyestes killing their half-brother, Chrysippus. This actually happens before the start of Seneca's play, with the brothers being banished by their father, Pelops, the son of Tantalus, because of this murder. This is mild compared to the bloodshed and unsavoury actions taken by Atreus in his revenge on Thyestes for seducing his wife, Aërope, and putting doubt on whether or not he is the father of his two sons, Agamemnon and Menelaus. Seneca's play ends horrifically with what has become known as the Thyestean Feast.

Thyestes is played by Thomas Henning, Atreus by

Toby Schmitz, and Chrysippus by

Chris Ryan, who, with his character being killed in the first scene, then plays a variety of other characters, male and female, for the remainder of the production. These three actors give strong performances, with the realism of the violence drawing occasional gasps from members of the audience. They give some quite hair-raising moments in this dark tale of lust, murder, rape, and revenge, and consistently impressive performances throughout.

This is not, of course, Seneca's play, but simply takes some of the plot elements as its source. The language is very much in a crude vernacular, often banal, with no shortage of expletives, and guns replace the weapons of two millennia ago. There are certainly none of Seneca's long speeches, either, which some might see as an advantage.

The central set, by Claude Marcos, allowing us to see through to the reactions of the other half of the audience, as they likewise see us, is an intriguing extra element to the production.

Reader Reviews

To post a comment, you must

register and

login.

Reviewed by Barry Lenny, Sunday 4th March 2018.

Reviewed by Barry Lenny, Sunday 4th March 2018. Reviewed by Barry Lenny, Sunday 4th March 2018.

Reviewed by Barry Lenny, Sunday 4th March 2018.