Reviewed by Barry Lenny, Sunday 15th March 2020.

Reviewed by Barry Lenny, Sunday 15th March 2020.

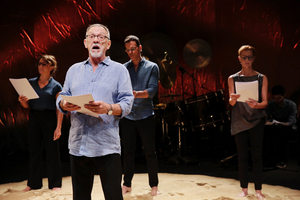

William Zappa has adapted Homer's 8th Century BC epic poem, The Iliad, drawing on numerous translations, and also directed this work,

The Iliad - Out Loud, to create a performance piece for four actors, including himself, plus two musicians, Michael Askill, on percussion, and Hamed Sadeghi, playing the lute-like Persian oud, and the tar. The other three actors are Heather Mitchell, Blazey Best, and Socratis Otto. It is a bold and imaginative venture.

Zappa also introduces and comments on the work at the start of each part, as well as providing a very brief précis of what happened in earlier parts for the second and third stages. Zappa was ably assisted in the translating and editing by Emeritus Professor Elizabeth Minchin FAHA. There are occasional sprinklings of modern language, and a few expletives.

Although attributed to Homer, it is agreed by experts that some of the sections were written by unknown others. Zappa ignored one book completely, Book 10, and gave brief summaries of others, so only a certain number of the books were actually given the full treatment by the four actors.

In case you were not aware, by the way, it all takes place not far from ANZAC Cove, the site of a much more recent battle.

If you were thinking that I would begin my review with a fully detailed synopsis of Homer's entire epic poem, you were very, very much mistaken. It all takes place during the last couple of weeks of the ten-year-long war between Greek forces and the city of Troy, a war that started when Paris took Helen, the wife of Menelaus of Sparta, to live with him in Troy (Ilias).

It is important to be aware, though, that, although the gods are immortal, they are also very human, with all of the prejudices, lusts, frailties, moral lapses, and other qualities, good and bad, that humans have, and they cannot seem to resist interfering in human affairs. The gods interfere many times in the war, favouring one side or the other, like two opposing groups of supporters at a sporting event.

They even interbreed with humans. As an example, the father of Achilles was Peleus, king of the Myrmidons, but his mother was Thetis, a nereid, or sea nymph. This makes Achilles a demigod. Peleus was, in turn, also a demigod in his own right, as a grandson of Zeus, the god of sky and thunder, and the ruler of all of the gods on Mount Olympus.

Incestuous relationships were, apparently, not a problem either, since one of the wives of Zeus, Hera, was his sister. Polygamy was also not a problem. She was one of his seven immortal wives (Metis, Themis, Eurynome, Demeter, Mnemosyne, Leto, and Hera), his principal wife, the goddess of women, marriage and the family, and known for her jealousy.

Aside from the main conflict, there is a sub-plot that causes antagonism with the Greek ranks. The Trojan priest of Apollo, Chryses, calls on his god to bring down a plague on the Greeks because Agamemnon has taken his daughter, Chryseis, as a war prize. The plague can only be stopped by his daughter's return. Agamemnon eventually, and reluctantly, agrees to her release, but only by taking another female war prize, Briseis, from her captor, Achilles, as a replacement. Achilles withdraws his army, the Myrmidons, from the battle in retaliation. This, of course, changes the balance in the battle.

There are myriad websites that will give you more details, or you could actually read one of the readily available translations, perhaps followed by Homer's other major work, The Odyssey, and even Virgil's Aeneid.

In front of a heavily textured bronze coloured screen, the stage was set with a mass of percussion instruments at the rear, surrounding Michael Askill, including timpani, assorted drums, cymbals, tam-tams (flat-faced gongs), and numerous small percussion, with a seat placed nearby for Hamed Sadeghi.

Centre stage, there was a large circle of sand, contoured differently for each of the three parts, and chairs that the performers moved as needed. The set and costume design was by Mel Liertz and, although the costuming was simple, but effective, the lighting, by

Matt cox, was complex, and played a very important part.

From light percussion and brief melodic motifs from the oud or the tar, behind low-key parts of the story, to rumbling bass drums and tom-toms with no melodic material, for the warlike sections and occasional silences, the accompaniment serves as a wordless Greek Chorus.

In front of the musicians, the four performers deliver their lines, the bulk of the performance carried by William Zappa, who delivers most of the narrative sections as well as his own commentaries, whilst all four portray the many characters, and contribute to the documentary, too. Interestingly, a particular character was not always played by the same actor, and roles were not distributed to the cast according to gender. This was another bold move, but this is what we expect from Adelaide Festival performances, events that go beyond the ordinary.

This was a mighty effort from all involved, and from audiences, too, for that matter. There were feats of endurance on both sides of the footlights. There was the occasional stumble in delivery, a few characterisations could have been more imposing, some were overacted, and one might argue about the editing here and there but, in nine hours of performance of such a complex and innovative work, a few quibbles could be overlooked.

When all is said and done, this is an important piece of theatre, bringing one of the Classics into the present and making it accessible to everybody through performance by a dedicated and committed group of likeminded people. It breathes new life into an ancient story and makes it relevant to the modern world.

There are a few times, such as the long list of boats and men who came to the war, something often glossed over when reading the Iliad, that make the performance seem a little like an academic lecture but, thankfully, without a written examination to follow, in spite of the venue.

The biggest drawback was that choice of venue, Scott Theatre. It was, long ago, effectively closed as a performance venue by the University, and repurposed as a lecture theatre. The current seats, with their flip-up desk flaps, are not designed for comfort, and are absolutely terrible for use over such a prolonged period of time.

The auditorium also became increasingly stuffier as the day wore on, not having been aired between the three parts, and with no air-conditioning turned on. With the cast seated for a long period in the second part, simply reading their scripts, combined with that stuffy atmosphere, it became very soporific, creating a challenge to concentrate on the complex text and, even, to simply stay awake. By part three it was uncomfortably warm and oppressive, making me feel unwell, and then leg cramp set in from the cumulative effect of the hours in those seats, forcing me to vacate mine and spend the remainder of the evening standing at the back of the auditorium.

In retrospect, I feel that it would have been better had the performances been spread over a number of evenings, rather than presenting it as such a marathon, starting at 11am and ending at 11pm. It was such an enormous amount to absorb in such a short time, aside from any discomfort, and time for reflection would have been advantageous.

Reader Reviews

To post a comment, you must

register and

login.

Reviewed by Barry Lenny, Sunday 15th March 2020.

Reviewed by Barry Lenny, Sunday 15th March 2020. Reviewed by Barry Lenny, Sunday 15th March 2020.

Reviewed by Barry Lenny, Sunday 15th March 2020.