Trending Stories

Recommended for You

Washington National Opera Announces Plans to Leave the Kennedy Center

The company has performed at the Kennedy Center since the venue opened in 1971.

Jim Parsons, Deborah Cox, Frankie Grande and Constantine Rousouli Join TITANIQUE Broadway Cast

They join the previously announced Marla Mindelle, who will lead the Broadway company as Celine Dion.

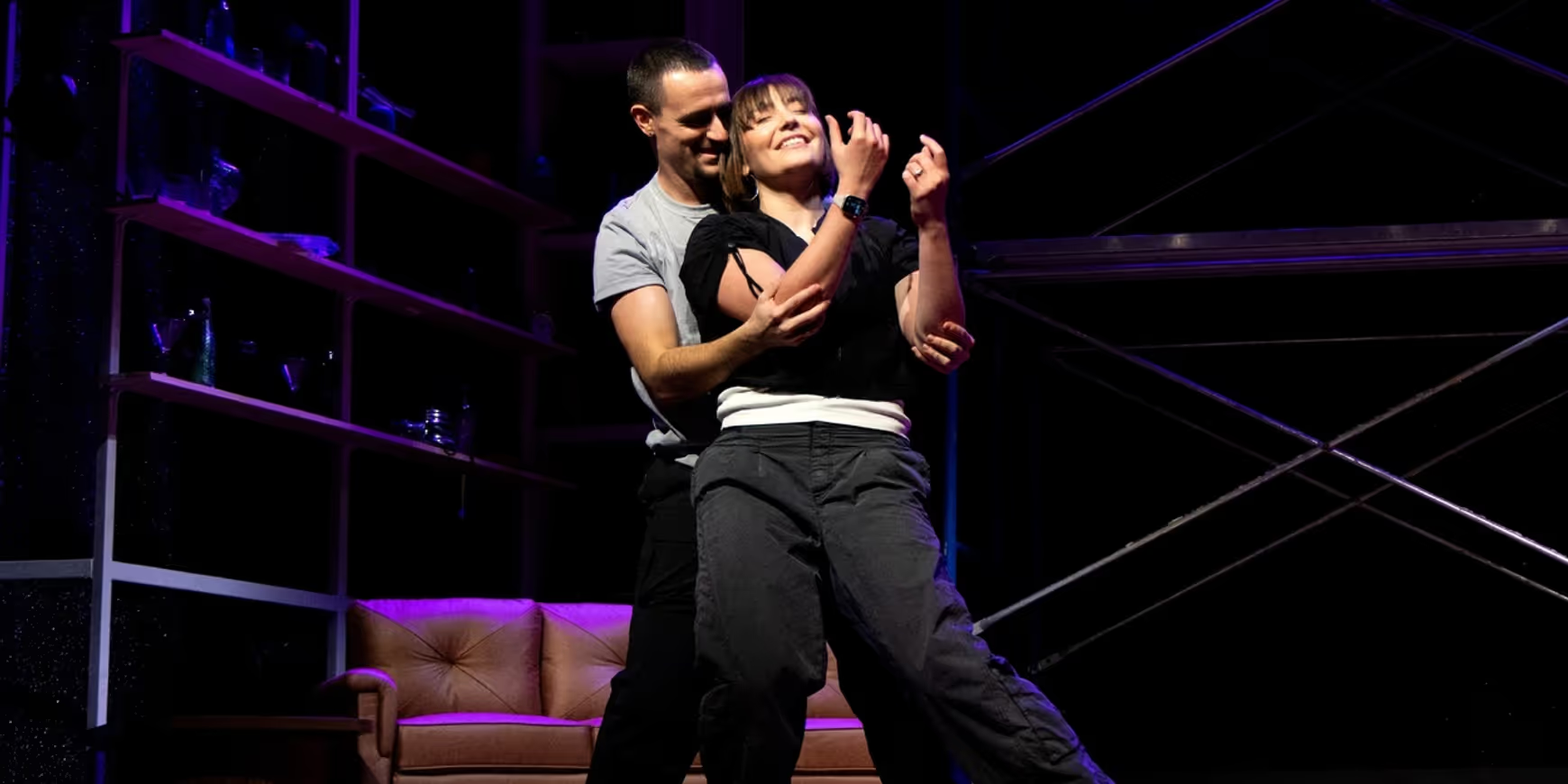

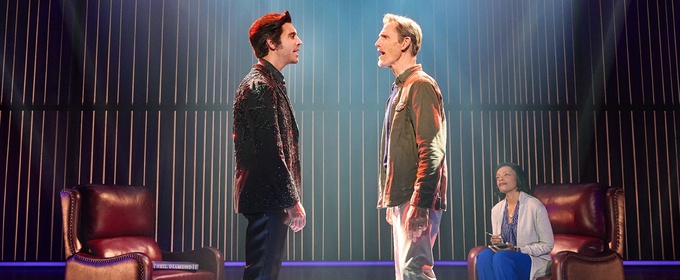

Review Roundup: Carrie Coon, Namir Smallwood and More Star in BUG on Broadway

The sci-fi thriller written by Tony Award and Pulitzer Prize winner Tracy Letts is directed by Tony Award winner David Cromer.

Keri René Fuller and Emma Flynn to Join WICKED on Broadway

Lencia Kebede (Elphaba) and Allie Trimm (Glinda) will play their final performances in March.

Ticket Central

West End

Photos: I'M SORRY, PRIME MINISTER in Rehearsal

The final chapter in the evergreen comedy series is transferring to the Apollo Theatre from 30 January

The final chapter in the evergreen comedy series is transferring to the Apollo Theatre from 30 January

New York City

Interview: MD Alexa Tarantino Talks DUKE IN AFRICA at Jazz At Lincoln Center

The January 15-17 show pays tribute to the influence of African music on the work of Duke Ellington

The January 15-17 show pays tribute to the influence of African music on the work of Duke Ellington

United States

Full Cast Set For NEWSIES at the Argyle Theatre

The production is directed by Tommy Ranieri, choreographed by Trent Soyster, with musical direction by Jonathan Brenner.

The production is directed by Tommy Ranieri, choreographed by Trent Soyster, with musical direction by Jonathan Brenner.

International

ENHYPEN Unveil Tracklist for Forthcoming Mini-Album 'THE SIN : VANISH'

THE SIN : VANISH comprises 11 tracks in total, including four narration tracks, one skit, and six songs that unfold sequentially rather than as standalone pieces.

THE SIN : VANISH comprises 11 tracks in total, including four narration tracks, one skit, and six songs that unfold sequentially rather than as standalone pieces.