Trending Stories

Recommended for You

Playlist: New Year, New You!

Check out 50 showtunes that will leave you feeling like a brand-new you!

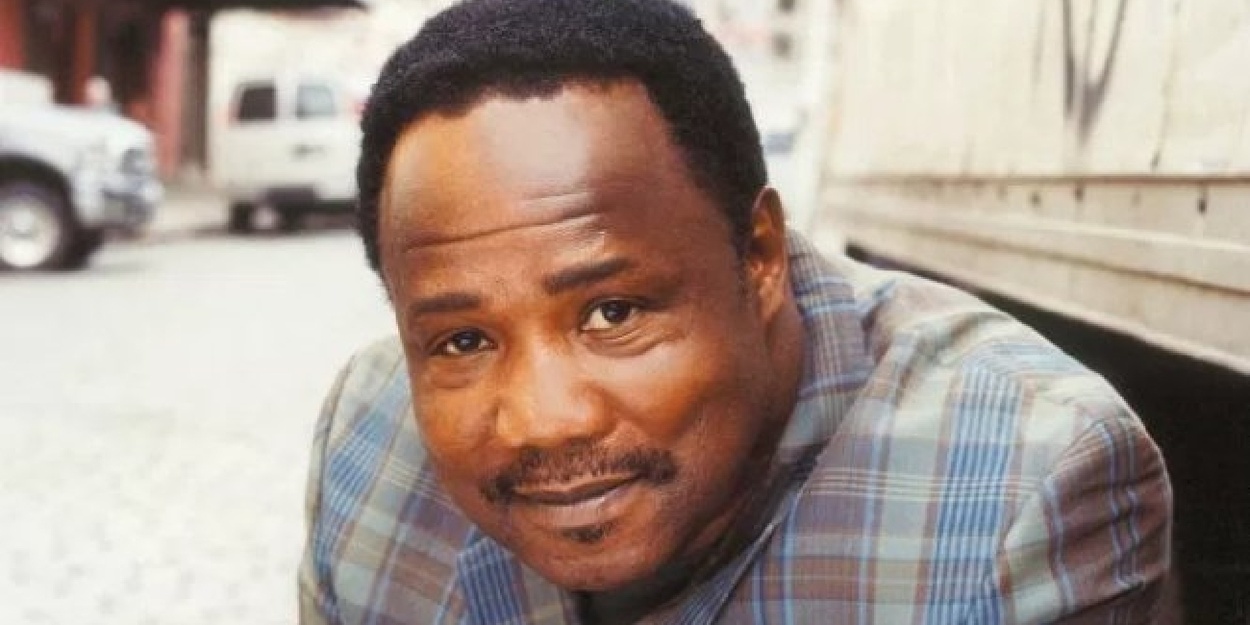

Broadway Alum Bret Hanna-Shuford Passes Away at 46

His husband, Stephen Hanna, confirmed the news on their social media.

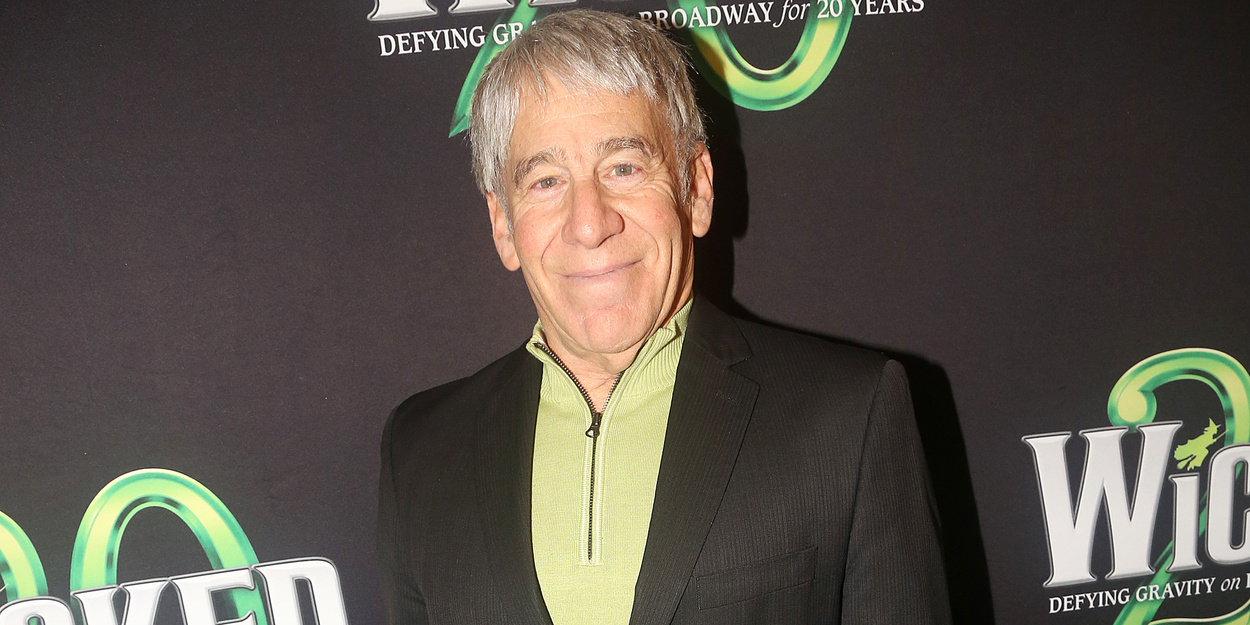

Video: Mandy Patinkin Leads 'Somewhere Over the Rainbow' at Mamdani's Inauguration

Mayor Mamdani's inaugural committee includes familiar theater faces like Cole Escola, Cynthia Nixon, John Turturro, and Julio Torres.

Videos: Jennifer Lopez Sings GYPSY, FUNNY GIRL & More in Las Vegas Residency

Currently running at The Colosseum at Caesars Palace, the show infuses Broadway standards with some of her greatest hits.

Ticket Central

Industry

West End

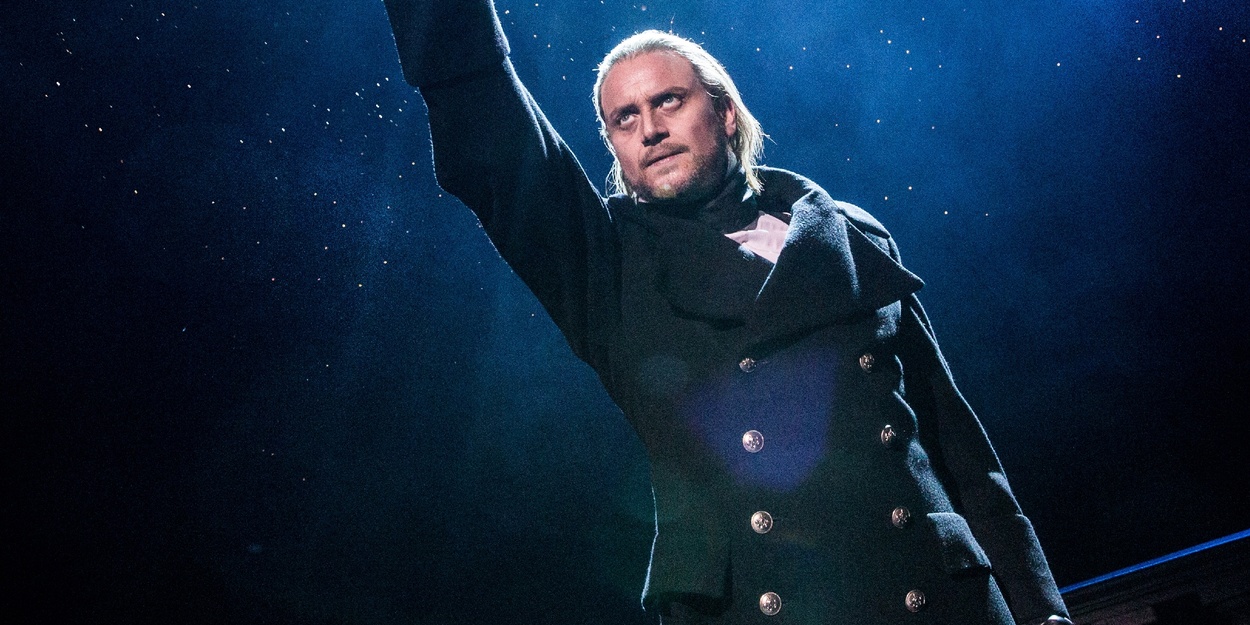

Lucie Jones Will Return to LES MISERABLES in the West End

Jones will play Fantine, a role she has already performed in the West End and more recently on the World Tour Arena Spectacular.

Jones will play Fantine, a role she has already performed in the West End and more recently on the World Tour Arena Spectacular.

New York City

Trans Musician & Tech CEO Michele Bettencourt's VAMPIRE TIME to Play NY's Cutting Room

The performance is on January 26.

The performance is on January 26.

United States

Interview: Chase Del Rey of ACTING FOR MUSICAL THEATRE WORKSHOP

This will take place on January 11, 2026

This will take place on January 11, 2026

International

Daniele Gatti Will Lead the Hong Kong Philharmonic in Guangzhou

The HK Phil will perform Mahler's Seventh Symphony in Guangzhou.

The HK Phil will perform Mahler's Seventh Symphony in Guangzhou.