Trending Stories

Recommended for You

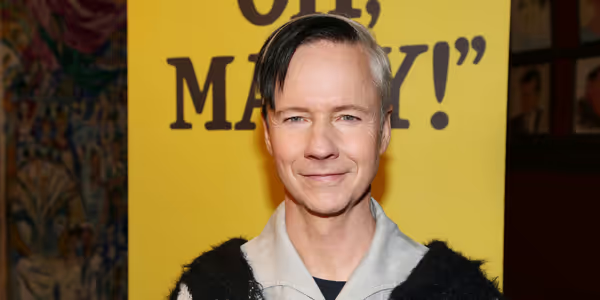

Maya Rudolph Will Make Broadway Debut in OH, MARY!

Rudolph will join the company as “Mary Todd Lincoln” on Tuesday, April 28, 2026 for a limited 8-week engagement through June 20, 2026.

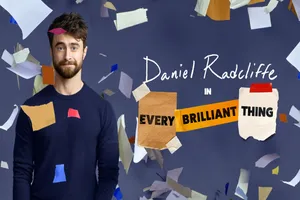

Review Roundup: Tony-Winner Daniel Radcliffe Stars in EVERY BRILLIANT THING on Broadway

Every Brilliant Thing is now in performances at The Hudson Theatre.

Second Round Voting Open For BroadwayWorld's Best Movie Musical Of All Time Bracket

Voting ends at 11:59 PM on Sunday, March 15th, 2026.

Photos: Jon Bernthal, Ebon Moss-Bachrach, & More in DOG DAY AFTERNOON

The play is written by Pulitzer Prize winner Stephen Adly Guirgis and directed by two-time Olivier Award winner Rupert Goold.

Ticket Central

Industry

West End

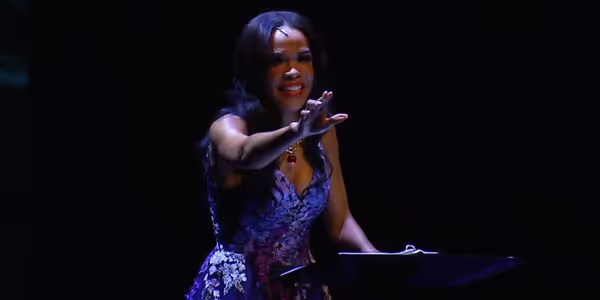

Review: TURN IT OUT WITH TILER PECK AND FRIENDS, Sadler's Wells

The New York City Ballet star returns to London

The New York City Ballet star returns to London

New York City

Interview: Composer Jeff Beal Premieres Latest Work with Death of Classical for MS Awareness Month

See the world premiere of Beal's latest work on 3/26 and 3/27 in an intimate concert at the Crypt Under the Church of the Intercession presented by Death of Classical

See the world premiere of Beal's latest work on 3/26 and 3/27 in an intimate concert at the Crypt Under the Church of the Intercession presented by Death of Classical

United States

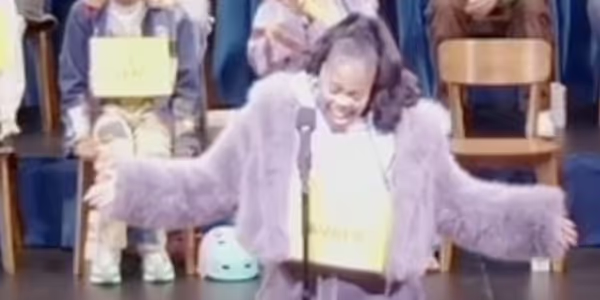

TUTS Will Stage HADESTOWN: TEEN EDITION with Houston's Young Talent

Houston's young performers will present a captivating rendition of HADESTOWN: TEEN EDITION at TUTS

Houston's young performers will present a captivating rendition of HADESTOWN: TEEN EDITION at TUTS

International

Review: BLOOD RELATIONS at The Gladstone Theatre

Like last year’s Silent Sky, Three Sisters Theatre Company presents a confident and compelling piece of theatre that tells the story of a strong female historical figure.

Like last year’s Silent Sky, Three Sisters Theatre Company presents a confident and compelling piece of theatre that tells the story of a strong female historical figure.

.png?format=auto&width=300)