Trending Stories

Recommended for You

Additional Cast Joins Nathan Lane, Laurie Metcalf, and More in DEATH OF A SALESMAN

The cast includes K. Todd Freeman (Charley), Jonathan Cake (Ben Loman), John Drea (Howard), Michael Benjamin Washington (Bernard), and more.

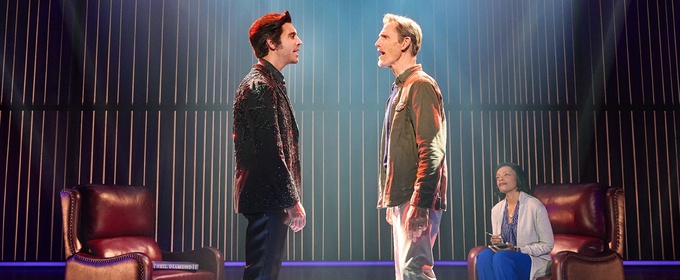

THE FANTASTICKS Will Be Reimagined as a Gay Love Story For Broadway

The production features a revised book and lyrics by Tom Jones and music by Harvey Schmidt

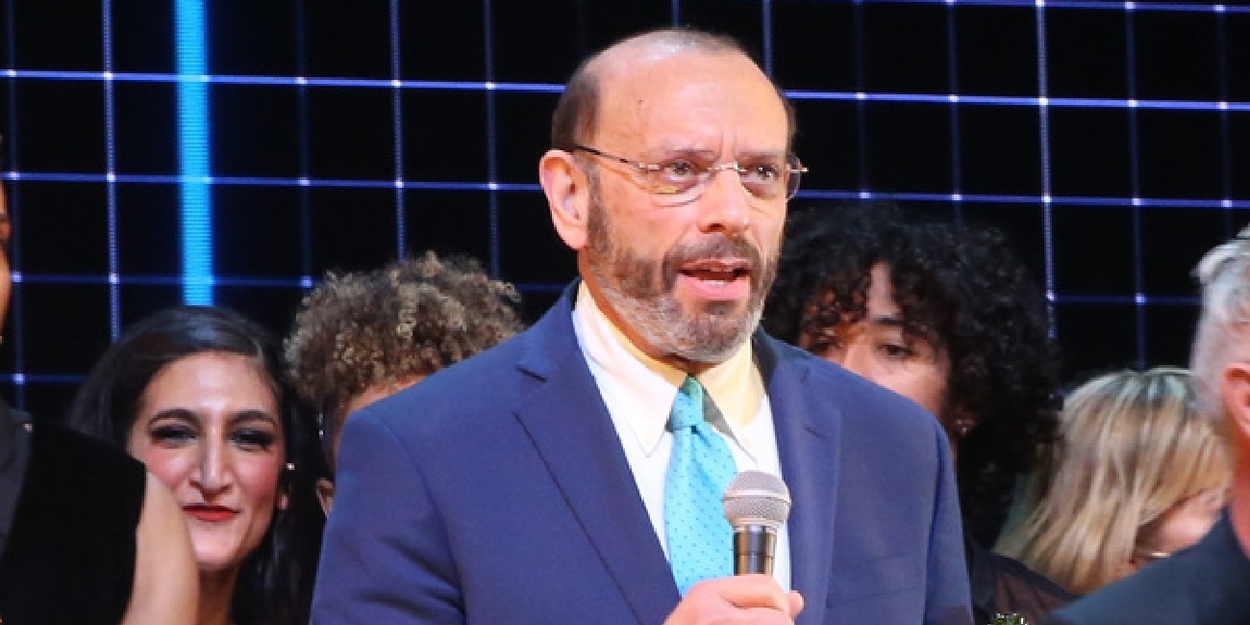

Interview: Frank Wildhorn on His Global Career

Wildhorn discusses his projects including Chimney Town, Death Note, his new symphony 'Vienna' and more!

Broadway Grosses: Week Ending 1/4/26 - 313,513 Total Tickets Sold

The highest grossing shows were Hamilton and Wicked.

Ticket Central

Industry

West End

PARANORMAL ACTIVITY Extends West End Run For a Second Time

Patrick Heusinger and Melissa James are currently reprising their Leeds Playhouse roles as 'James' and 'Lou.'

Patrick Heusinger and Melissa James are currently reprising their Leeds Playhouse roles as 'James' and 'Lou.'

New York City

NIGHT STORIES to Conclude Limited Run This Week at Wild Project

Starring Shane Baker and Miryem-Khaye Seigel, NIGHT STORIES is directed by Moshe Yassur with Beate Hein Bennett.

Starring Shane Baker and Miryem-Khaye Seigel, NIGHT STORIES is directed by Moshe Yassur with Beate Hein Bennett.

United States

Norbert Leo Butz and More to Star in THE RECIPE at La Jolla Playhouse

The cast features Jill Abramovitz, Christina Kirk, Rami Margron and more.

The cast features Jill Abramovitz, Christina Kirk, Rami Margron and more.

International

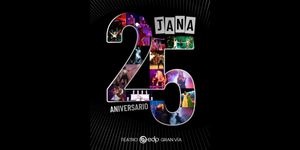

JANA: Un Cuarto de Siglo de Magia, Formación y Éxito Internacional

La historia de una compañía con más de 50 premios nacionales que ha convertido su pasión por los musicales en un referente mundial.

La historia de una compañía con más de 50 premios nacionales que ha convertido su pasión por los musicales en un referente mundial.

.jpg?format=auto&width=606)