Trending Stories

Recommended for You

Washington National Opera Announces Plans to Leave the Kennedy Center

The company has performed at the Kennedy Center since the venue opened in 1971.

Jim Parsons, Deborah Cox, Frankie Grande and Constantine Rousouli Join TITANIQUE Broadway Cast

They join the previously announced Marla Mindelle, who will lead the Broadway company as Celine Dion.

Review Roundup: Carrie Coon, Namir Smallwood and More Star in BUG on Broadway

The sci-fi thriller written by Tony Award and Pulitzer Prize winner Tracy Letts is directed by Tony Award winner David Cromer.

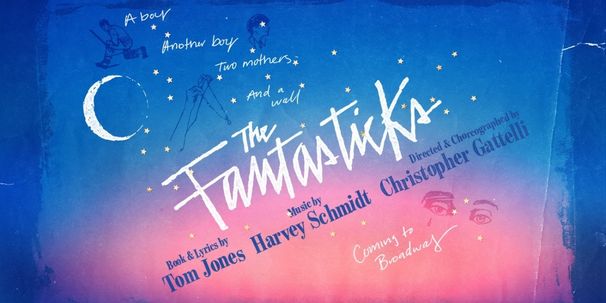

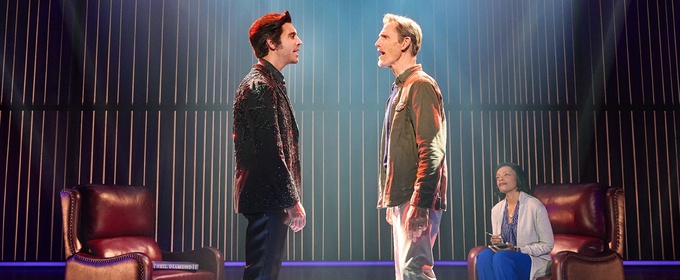

THE FANTASTICKS Will Be Reimagined as a Gay Love Story For Broadway

The production features a revised book and lyrics by Tom Jones and music by Harvey Schmidt

Ticket Central

West End

GET TECHNICAL! Behind The Scenes of MOULIN ROUGE! THE MUSICAL Returns For 2026

Moulin Rouge! will once again open its doors to give anyone aspiring to a career in theatre a glimpse behind the curtain of the multi award-winning production.

Moulin Rouge! will once again open its doors to give anyone aspiring to a career in theatre a glimpse behind the curtain of the multi award-winning production.

New York City

Review: Adam Pascal & Anthony Rapp Celebrate Friendship and Legacy at 54 Below

Whether you're a RENT-head or not, this hour-long concert was a joyful celebration of thrilling music, both deeply familiar and pleasantly unexpected

Whether you're a RENT-head or not, this hour-long concert was a joyful celebration of thrilling music, both deeply familiar and pleasantly unexpected

United States

Steely Dane Comes to Des Moines Performing Arts Center

Shows consist of hits and deep cuts and sometimes even complete albums and are sure to have you out of your seats singing along.

Shows consist of hits and deep cuts and sometimes even complete albums and are sure to have you out of your seats singing along.

International

RIDDIM & RHYMES Comes to Esplanade This Week

The event features performances from Amir Mansor, ARDY, Flique Mohamad and Nurhakeem.

The event features performances from Amir Mansor, ARDY, Flique Mohamad and Nurhakeem.