Trending Stories

Recommended for You

Washington National Opera Announces Plans to Leave the Kennedy Center

The company has performed at the Kennedy Center since the venue opened in 1971.

Jim Parsons, Deborah Cox, Frankie Grande and Constantine Rousouli Join TITANIQUE Broadway Cast

They join the previously announced Marla Mindelle, who will lead the Broadway company as Celine Dion.

Review Roundup: Carrie Coon, Namir Smallwood and More Star in BUG on Broadway

The sci-fi thriller written by Tony Award and Pulitzer Prize winner Tracy Letts is directed by Tony Award winner David Cromer.

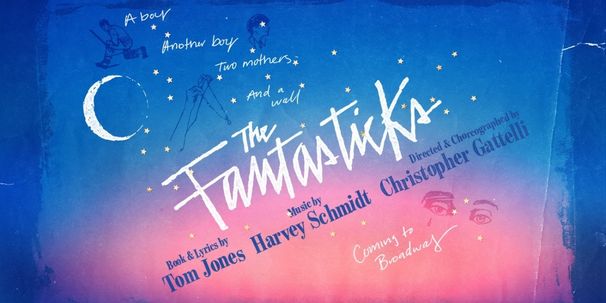

THE FANTASTICKS Will Be Reimagined as a Gay Love Story For Broadway

The production features a revised book and lyrics by Tom Jones and music by Harvey Schmidt

Ticket Central

West End

Review: HIGH NOON starring Billy Crudup, Harold Pinter Theatre

Starry cast delivers superb adaptation of iconic western

Starry cast delivers superb adaptation of iconic western

New York City

Interview: Marisa Caruso Explores Mental Health in HOW TO MAKE A DOLL at Brooklyn Art Haus

The 1/25 show is about dementia, family, and the transformative power of making something by hand

The 1/25 show is about dementia, family, and the transformative power of making something by hand

United States

Agatha Christie’s THE MOUSETRAP Comes to Fort Collins

Performances are January 10 through February 8.

Performances are January 10 through February 8.

International

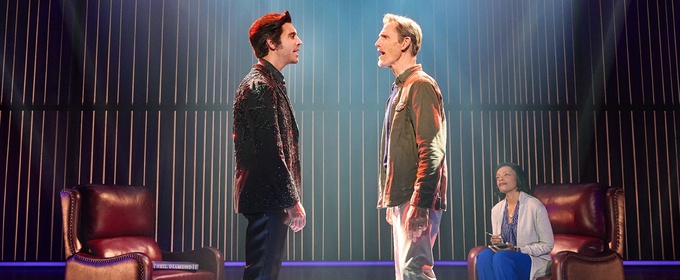

Interview: Aidan DeSalaiz of COMPANY at The Theatre Centre

Talk Is Free Theatre's immersive production takes on urban loneliness

Talk Is Free Theatre's immersive production takes on urban loneliness