Trending Stories

Recommended for You

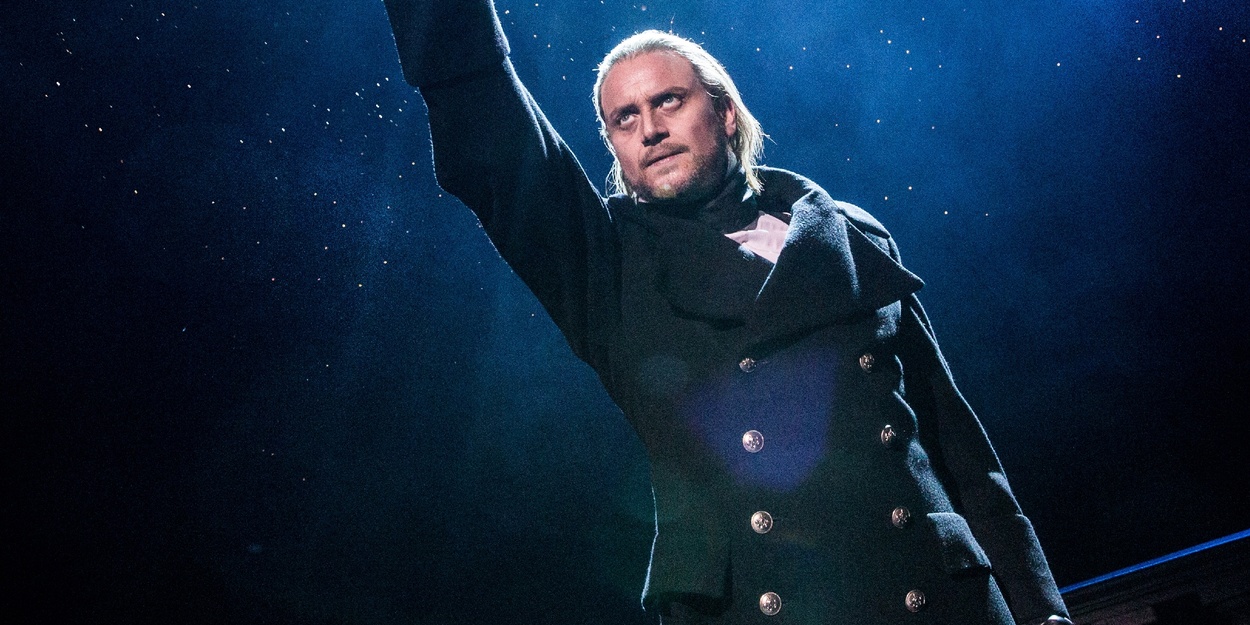

Top Viral Moments on Broadway in 2025: BOOP!, 'Hamilten,' & More

These Broadway moments went viral on social media this year.

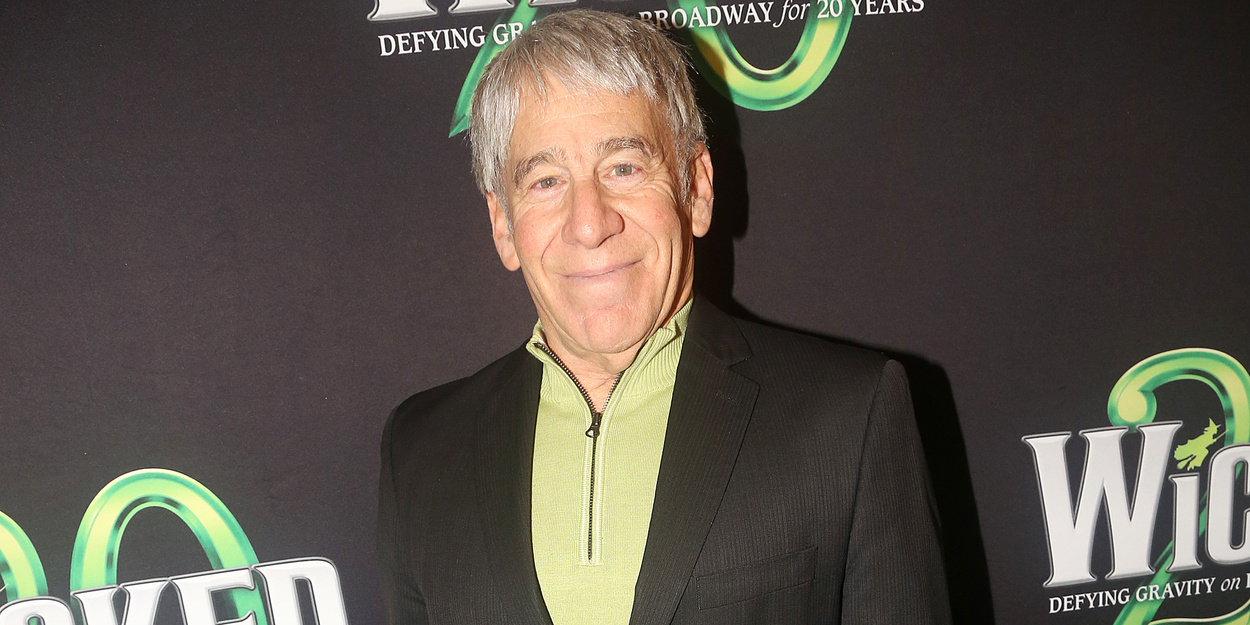

Broadway Grosses: Week Ending 12/28/25 - WICKED Reclaims Top Spot During Holidays

View the latest Broadway Grosses

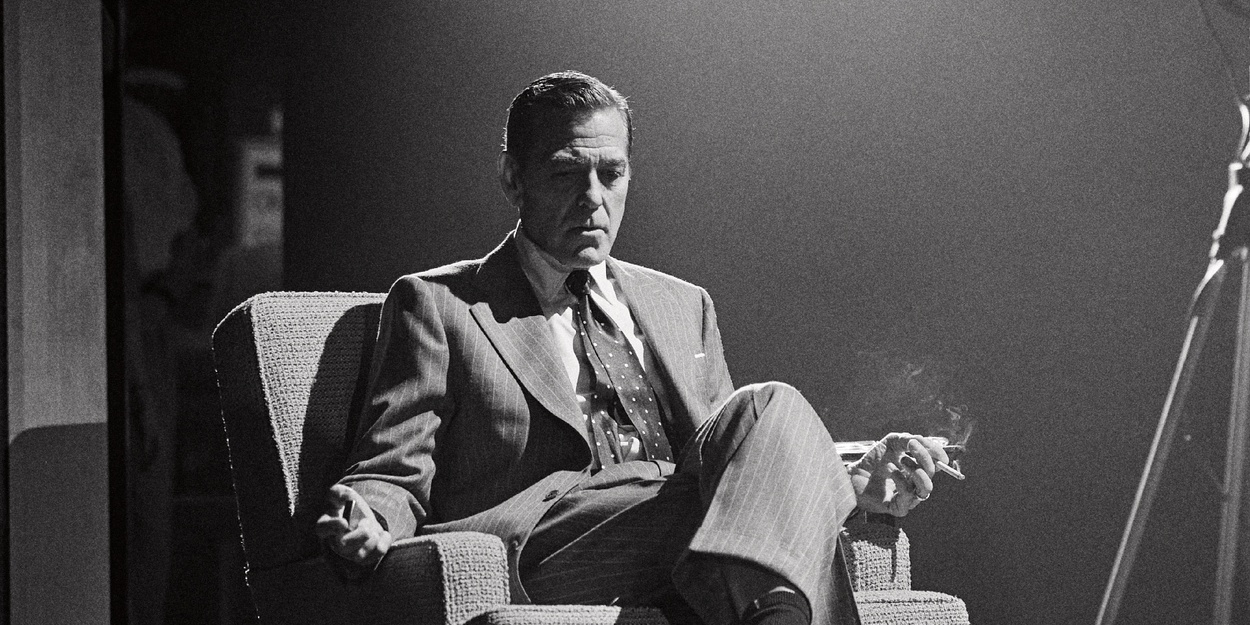

Recap the Broadway Debuts of 2025

2025's featured Broadway debuts included Christopher Lowell in Cult of Love, Amalia Yoo in John Proctor is the Villain, and more!

Playlist: New Year, New You!

Check out 50 showtunes that will leave you feeling like a brand-new you!

Ticket Central

Industry

West End

Review: THE RIVALS, Orange Tree Theatre

Tom Littler shows how to make a 250-year-old play feel both fresh and fun

Tom Littler shows how to make a 250-year-old play feel both fresh and fun

New York City

Trans Musician & Tech CEO Michele Bettencourt's VAMPIRE TIME to Play NY's Cutting Room

The performance is on January 26.

The performance is on January 26.

United States

Braddon Mendelson's PASSING WIND Blows Into Santa Clarita with a Comedic Gust Of Theatrical Farce

The production runs March 13-22.

The production runs March 13-22.

International

Katrina Mathers Returns to Melbourne International Comedy Festival with New Work

Performances begin March 26.

Performances begin March 26.

.jpg)

.jpg?format=auto&width=606)