Trending Stories

Recommended for You

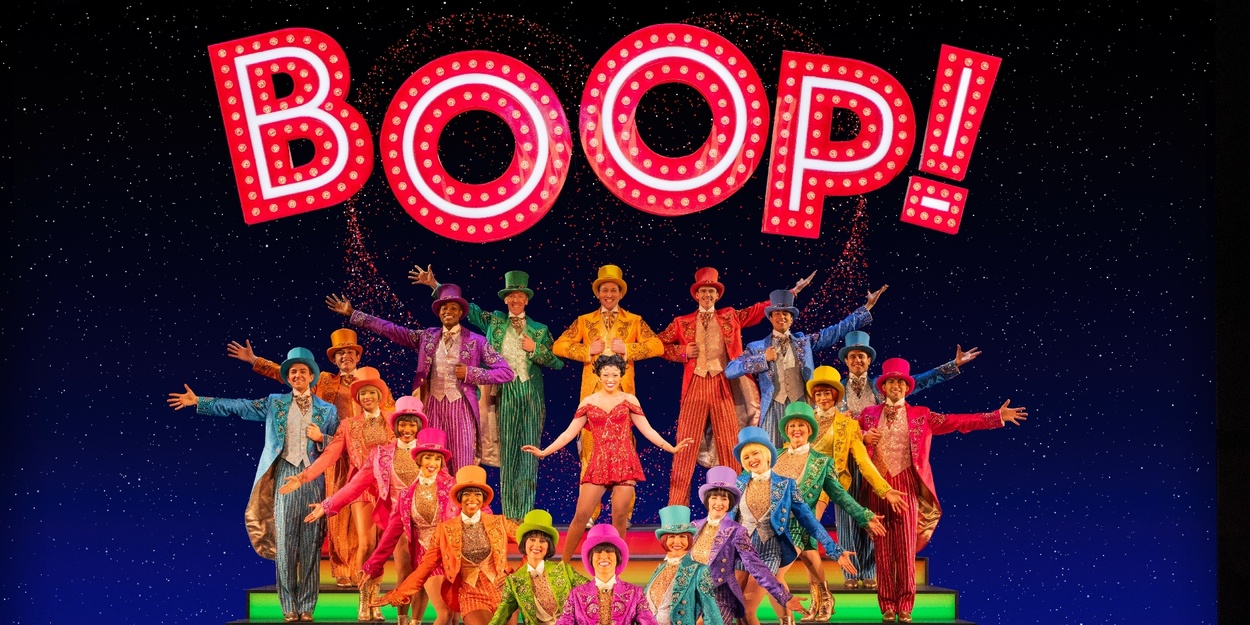

Top Viral Moments on Broadway in 2025: BOOP!, 'Hamilten,' & More

These Broadway moments went viral on social media this year.

Additional Cast Joins Nathan Lane, Laurie Metcalf, and More in DEATH OF A SALESMAN

The cast includes K. Todd Freeman (Charley), Jonathan Cake (Ben Loman), John Drea (Howard), Michael Benjamin Washington (Bernard), and more.

From Hawkins to Broadway: A Guide to STRANGER THINGS Cast Members on Stage

Find out which Broadway and stage stars appear in the hit Netflix series.

Interview: Frank Wildhorn on His Global Career

Wildhorn discusses his projects including Chimney Town, Death Note, his new symphony 'Vienna' and more!

Ticket Central

Industry

West End

Photos: Sheridan Smith and Romesh Ranganathan in WOMAN IN MIND at the Duke of York’s Theatre

Romesh Ranganathan makes his West End stage debut in the role of Bill.

Romesh Ranganathan makes his West End stage debut in the role of Bill.

New York City

Best Cabaret in 2026: Patti LuPone, Laura Benanti & More

See some of the best can't-miss events of 2026 that will sell out weeks in advance

See some of the best can't-miss events of 2026 that will sell out weeks in advance

United States

Tickets for Chicago Theatre Week 2026 to go on Sale This Week

Participating theatres include Citadel Theatre, A Red Orchid Theatre, The Second City, and more.

Participating theatres include Citadel Theatre, A Red Orchid Theatre, The Second City, and more.

International

Fantasia Orchestra to Perform at Nottingham Royal Concert Hall

The performance will feature regular collaborator and long-time friend of the orchestra Jess Gilliam MBE.

The performance will feature regular collaborator and long-time friend of the orchestra Jess Gilliam MBE.