Trending Stories

Recommended for You

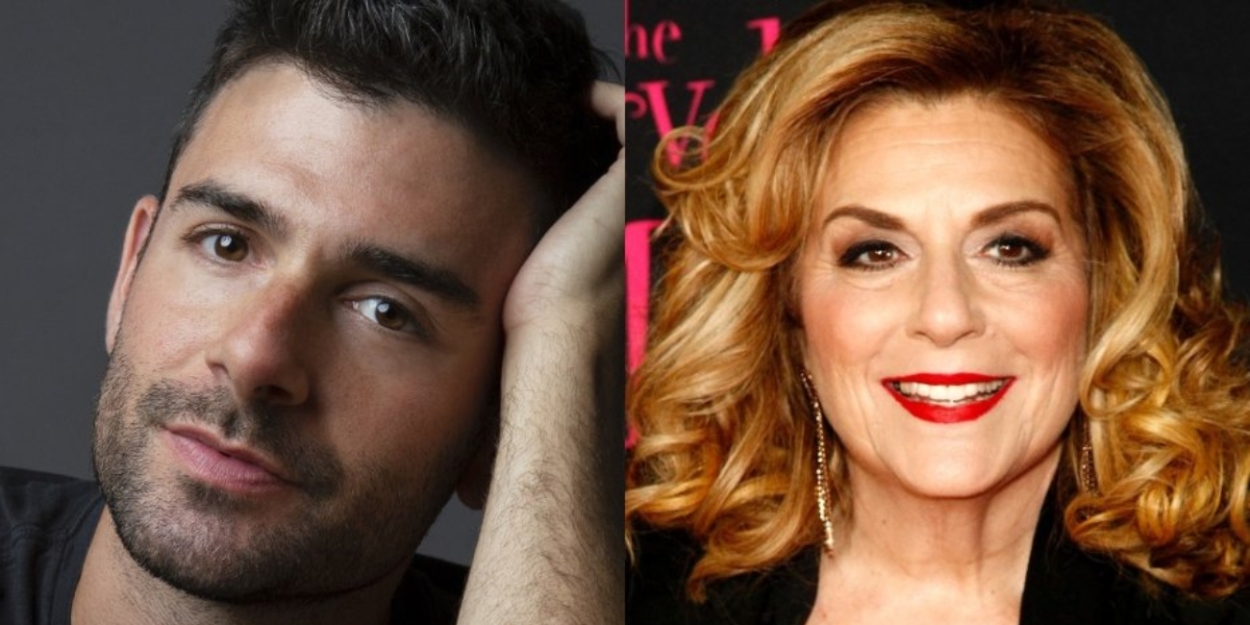

THE QUEEN OF VERSAILLES, Led By Kristin Chenoweth, Gets Broadway Theater and Dates

The new musical will open at the St. James Theatre in fall 2025.

Curtains Fall at the Kennedy Center: What Is Trump Doing and Why?

We're breaking down all of the latest updates from Trump's Kennedy Center takeover.

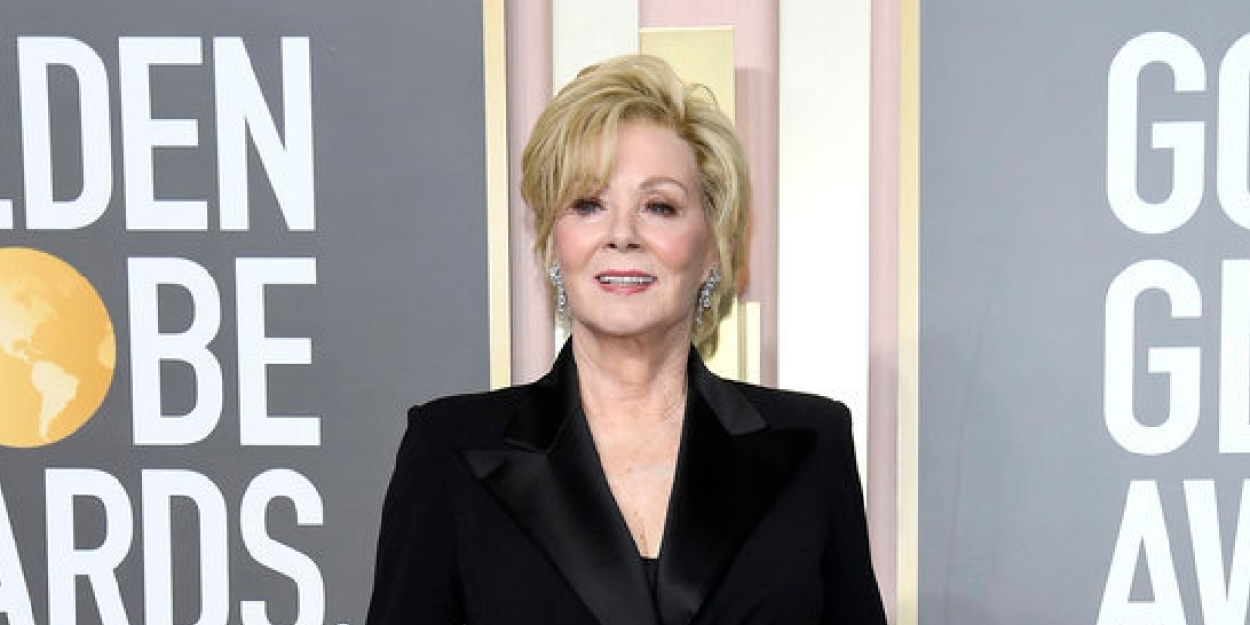

Jean Smart Will Return to Broadway in One-Woman Show CALL ME IZZY

The 12-week limited engagement will play Studio 54 from May 24 – August 17, 2025.

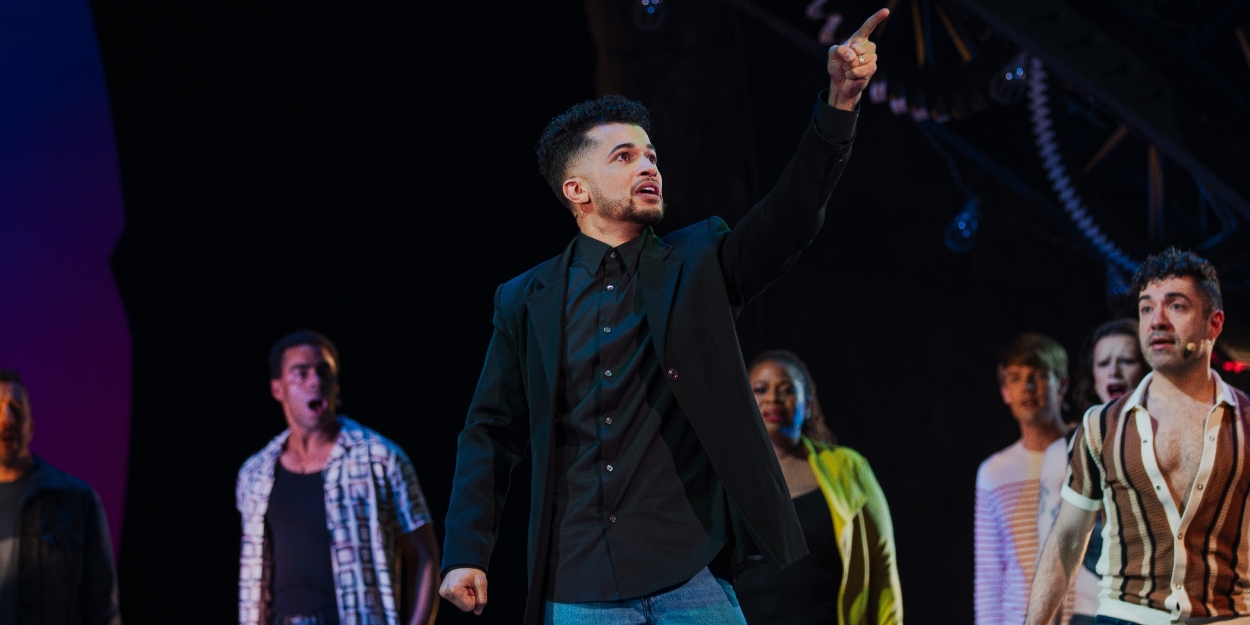

Meet the Cast of SMASH, Beginning Previews Tonight on Broadway

The production will officially open Thursday, April 10, 2025 at Broadway’s Imperial Theatre.

Ticket Central

Industry

West End

Review: THE LITTLE PRINCE, London Coliseum

Plenty of eye candy but little to feed the heart.

Plenty of eye candy but little to feed the heart.

New York City

Interview: Kim David Smith Celebrates New Album, MOSTLY MARLENE, at Joe's Pub

Smith will celebrate his new album’s release with a special New York concert at Joe’s Pub on 3/21, the night it comes out

Smith will celebrate his new album’s release with a special New York concert at Joe’s Pub on 3/21, the night it comes out

United States

Melissa Errico to Bring THE STORY OF A ROSE To D.C. Region

The production plays at the Rachel M. Schlesinger Concert Hall and Arts Center on May 7.

The production plays at the Rachel M. Schlesinger Concert Hall and Arts Center on May 7.

International

Rodgers & Hammerstein o el inicio de la época dorada de Broadway

Con la llegada de Cenicienta a España, revisamos el legado de la icónica pareja que revolucionó Broadway en los años 40.

Con la llegada de Cenicienta a España, revisamos el legado de la icónica pareja que revolucionó Broadway en los años 40.