Trending Stories

Recommended for You

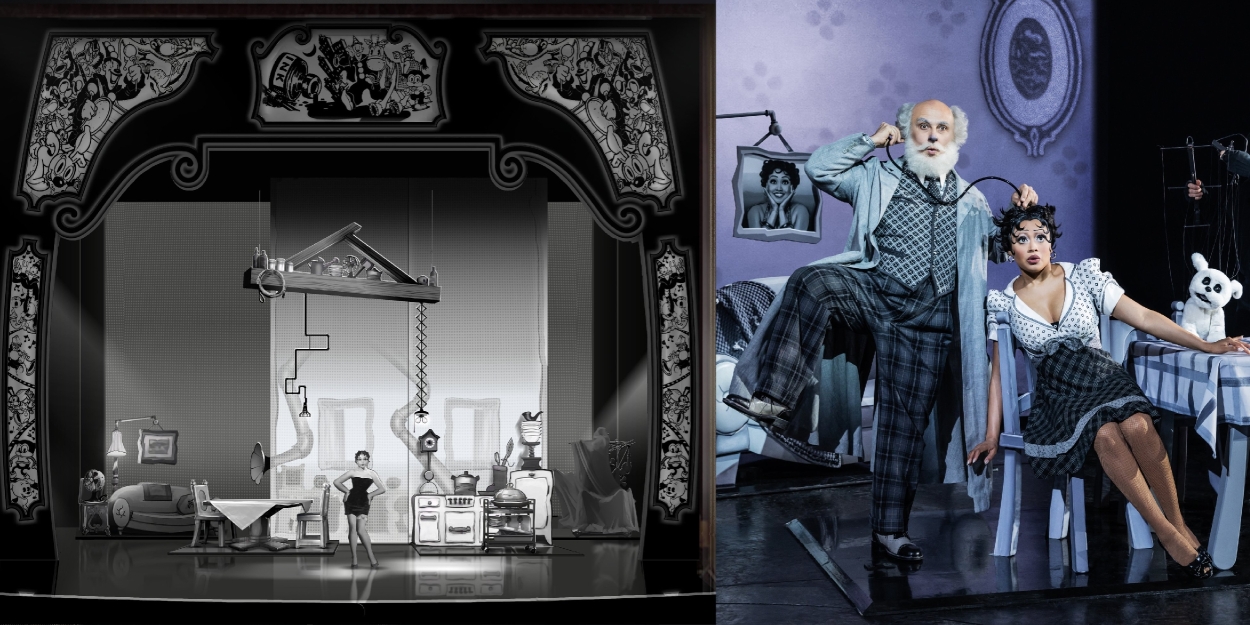

Review Roundup: Sarah Snook Stars In THE PICTURE OF DORIAN GRAY On Broadway

This new adaptation is written and directed by Kip Williams.

John Krasinski Will Lead ANGRY ALAN Off-Broadway

Sam Gold will direct the limited 10-week engagement.

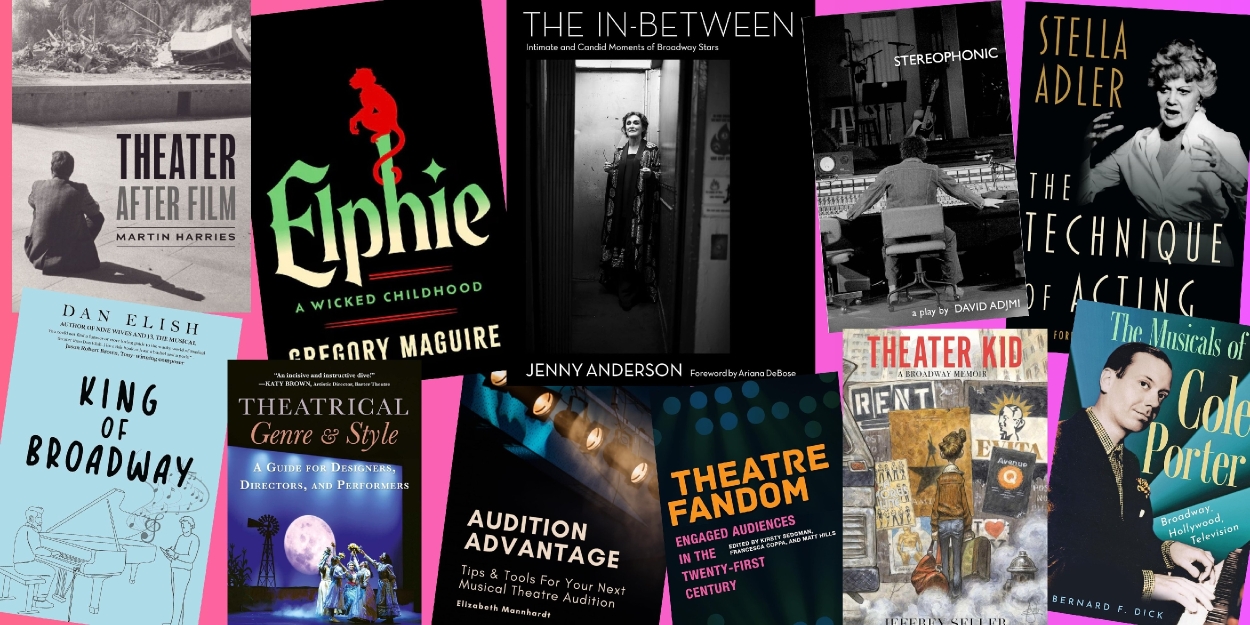

21 Theater Books for Your Spring 2025 Reading List

Broadway authors this season include Jeffrey Seller, Gregory Maguire and more.

Hugh Jackman, Liev Schreiber and More to Star in Audible Theater Plays

Up first is Hannah Moscovitch’s Sexual Misconduct of the Middle Classes, with Ella Beatty and Hugh Jackman.

Ticket Central

Industry

West End

Round 5 Voting Open for 2nd Annual Ultimate Best Musical Broadway Bracket

Which Best Musical is the ultimate Best Musical?

Which Best Musical is the ultimate Best Musical?

New York City

BroadwayWorld Cabaret Upcoming Show Roundup – Mar. 31 to Apr. 6

Some of our top picks for live cabaret shows and events to see in NYC this week

Some of our top picks for live cabaret shows and events to see in NYC this week

United States

Review: FAT HAM at Wilbury Theatre Group

The production runs through April 13.

The production runs through April 13.

International

Seven Dials Playhouse to Launch Inaugural Pride Season This June

The season will include a cowboy-clown mashup, a Celine Dion drag tribute and more.

The season will include a cowboy-clown mashup, a Celine Dion drag tribute and more.