Trending Stories

Recommended for You

2 Broadway Shows Close Today

All Out and Bug play their final performances on March 8, 2026.

CHESS, MAMMA MIA!, and RAGTIME Lead Nominations for the Inaugural Broadway Ensemble Awards

The first Broadway Ensemble Awards will honor chorus performers and creative teams across the 2025/2026 Broadway season.

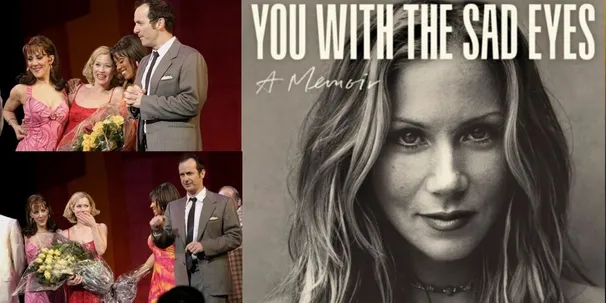

Christina Applegate Reveals She Put Up ‘Half a Million Bucks’ to Save Broadway’s SWEET CHARITY

“My agent said to me, ‘Either you’re the stupidest person I’ve ever met or you’re a f**king genius."

Second Round Voting Open For BroadwayWorld's Best Movie Musical Of All Time Bracket

Voting ends at 11:59 PM on Sunday, March 15th, 2026.

Ticket Central

Industry

West End

Review: THE BEEKEEPER OF ALEPPO, Richmond Theatre

A missed opportunity to get to the heart of this important story

A missed opportunity to get to the heart of this important story

New York City

Review: Lyrics & Lyricist's STARDUST: FROM TIN PAN ALLEY TO BROADWAY at 92NY

Lyrics & Lyricists explored music From Tin Pan Alley to Broadway 2/28 to 3/2. The series returns in June with the music of Alan & Marilyn Bergman

Lyrics & Lyricists explored music From Tin Pan Alley to Broadway 2/28 to 3/2. The series returns in June with the music of Alan & Marilyn Bergman

United States

Northlight Theatre Reveals Inaugural Season in the Company’s New Home in Downtown Evanston

The five-play 2026-2027 season, including three world premieres, opens with Jeffrey Hatcher’s The Front Page.

The five-play 2026-2027 season, including three world premieres, opens with Jeffrey Hatcher’s The Front Page.

International

RE:FORM Exhibition Explores Vietnamese Abstraction Post-Đổi Mới

The exhibition brings together five major figures from different generations.

The exhibition brings together five major figures from different generations.

.jpg?format=auto&width=600)