Trending Stories

Recommended for You

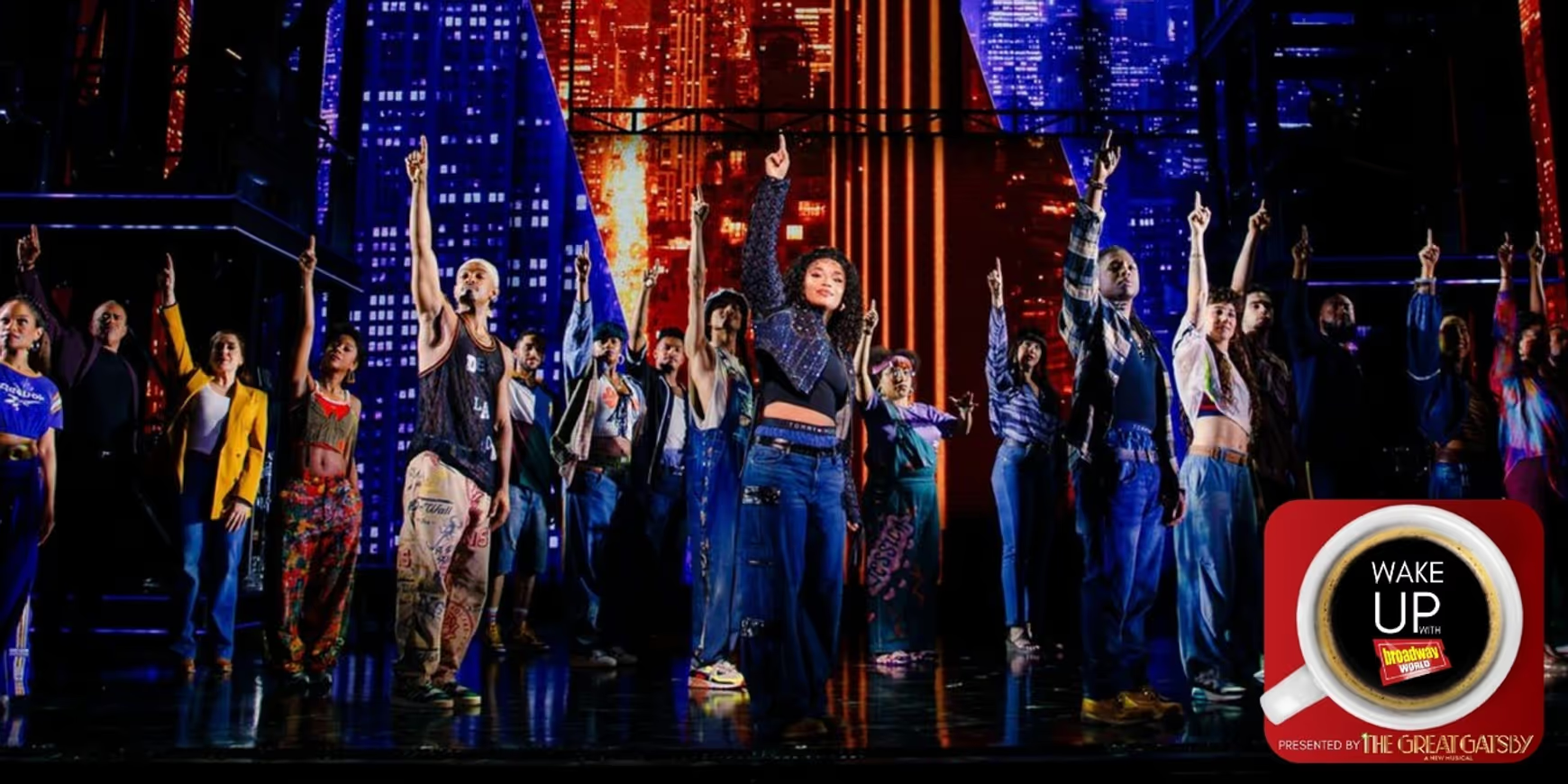

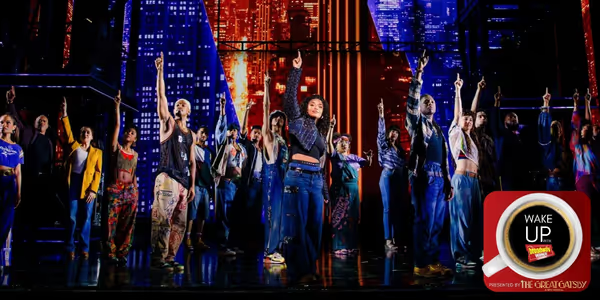

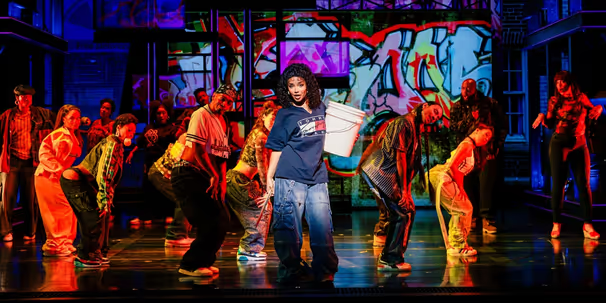

HELL'S KITCHEN Sets Broadway Closing Date

Brandon Victor Dixon, will return to the role of Davis beginning Tuesday, January 27th through the remainder of the run.

Keri René Fuller and Emma Flynn to Join WICKED on Broadway

Lencia Kebede (Elphaba) and Allie Trimm (Glinda) will play their final performances in March.

Joshua Colley, J. Harrison Ghee and More to Join HADESTOWN

The cast will feauture Jordan Tyson as 'Eurydice,' Gaby Moreno as 'Persephone,' and more.

Reeve Carney and Eva Noblezada Will Star in THE GREAT GATSBY

Noblezada originated the role of Daisy Buchanan on Broadway, and will return to star alongside her real-life husband Carney.

Ticket Central

West End

Mischief's CHRISTMAS CAROL GONE WRONG Will Be Filmed In Aylesbury

The show continues its UK tour after its sell-out West End run, visiting Nottingham Theatre Royal, the Aylesbury Waterside Theatre, and more.

The show continues its UK tour after its sell-out West End run, visiting Nottingham Theatre Royal, the Aylesbury Waterside Theatre, and more.

New York City

Review: Liz Callaway & Ann Hampton Callaway's BOOM Brings Memories to 54 Below

The 15th anniversary of "Boom!" runs January 14–17, 2026, at 54 Below, with performances at 7 PM.

The 15th anniversary of "Boom!" runs January 14–17, 2026, at 54 Below, with performances at 7 PM.

United States

John Mulaney Brings MISTER WHATEVER to New Orleans

In December 2024, Mulaney starred in the Broadway play “All In: Comedy About Love."

In December 2024, Mulaney starred in the Broadway play “All In: Comedy About Love."

International

LATE NIGHT EXTRAVAGANZA EYES WIDE SHUT Comes to Grand Théâtre de Genève

The company will host a “Best Dressed Spectator” category, allowing audiences to strut on the catwalk in front of a panel of judges.

The company will host a “Best Dressed Spectator” category, allowing audiences to strut on the catwalk in front of a panel of judges.