Trending Stories

Recommended for You

Additional Cast Joins Nathan Lane, Laurie Metcalf, and More in DEATH OF A SALESMAN

The cast includes K. Todd Freeman (Charley), Jonathan Cake (Ben Loman), John Drea (Howard), Michael Benjamin Washington (Bernard), and more.

Jim Parsons, Deborah Cox, Frankie Grande and Constantine Rousouli Join TITANIQUE Broadway Cast

They join the previously announced Marla Mindelle, who will lead the Broadway company as Celine Dion.

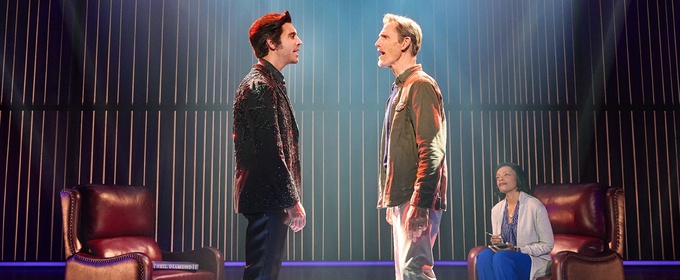

THE FANTASTICKS Will Be Reimagined as a Gay Love Story For Broadway

The production features a revised book and lyrics by Tom Jones and music by Harvey Schmidt

Interview: Frank Wildhorn on His Global Career

Wildhorn discusses his projects including Chimney Town, Death Note, his new symphony 'Vienna' and more!

Ticket Central

Industry

West End

PARANORMAL ACTIVITY Extends West End Run For a Second Time

Patrick Heusinger and Melissa James are currently reprising their Leeds Playhouse roles as 'James' and 'Lou.'

Patrick Heusinger and Melissa James are currently reprising their Leeds Playhouse roles as 'James' and 'Lou.'

New York City

NIGHT STORIES to Conclude Limited Run This Week at Wild Project

Starring Shane Baker and Miryem-Khaye Seigel, NIGHT STORIES is directed by Moshe Yassur with Beate Hein Bennett.

Starring Shane Baker and Miryem-Khaye Seigel, NIGHT STORIES is directed by Moshe Yassur with Beate Hein Bennett.

United States

Winners Announced For The 2025 BroadwayWorld Atlanta Awards

See who audiences selected as their favorites last season!

See who audiences selected as their favorites last season!

International

Stratford Festival 2026 Season Goes On Sale Saturday

Stratford Festival announces ticket sales for its 2026 season featuring a diverse lineup

Stratford Festival announces ticket sales for its 2026 season featuring a diverse lineup