Trending Stories

Recommended for You

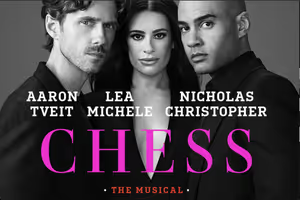

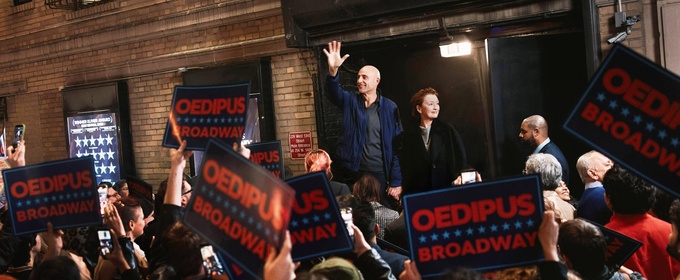

Tony Awards Eligibility Announced for BUG, CHESS, and More

Other productions discussed were: Oedipus; Two Strangers (Carry a Cake Across New York); and Marjorie Prime.

Complete Cast Announced for Year Two of STRANGER THINGS: THE FIRST SHADOW

Tony nominee Louis McCartney will play his final performance on Sunday, March 15.

Matthew Morrison Will Return to Broadway in JUST IN TIME

He will play a strictly limited 3-week engagement beginning Wednesday, April 1, 2026, at Circle in the Square Theatre.

Tom Hiddleston And Hayley Atwell To Star In Jamie Lloyd's MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING On Broadway

Jamie Lloyd will bring his acclaimed London production to Broadway for a 10-week run in fall 2026.

Ticket Central

West End

Review: WHAT I’D BE, Jack Studio

This new play by Tanieth Kerr centres on a pair of estranged sisters

This new play by Tanieth Kerr centres on a pair of estranged sisters

New York City

Town Hall to Host BLACK HISTORY MONTH CHORAL FESTIVAL Featuring Damien Sneed

Damien Sneed curates a celebration of African American musical heritage at The Town Hall

Damien Sneed curates a celebration of African American musical heritage at The Town Hall

United States

Video: Agatha Christie's AND THEN THERE WERE NONE at Fulton Theatre

The production runs through March 8th, 2026.

The production runs through March 8th, 2026.

International

Review: THE LAST FIVE YEARS at PumpHouse Theatre Auckland

This is a show you definitely should take the opportunity to get along to see — easily accessible at the PumpHouse Theatre, Auckland.

This is a show you definitely should take the opportunity to get along to see — easily accessible at the PumpHouse Theatre, Auckland.

.jpg?format=auto&width=300)