Trending Stories

Recommended for You

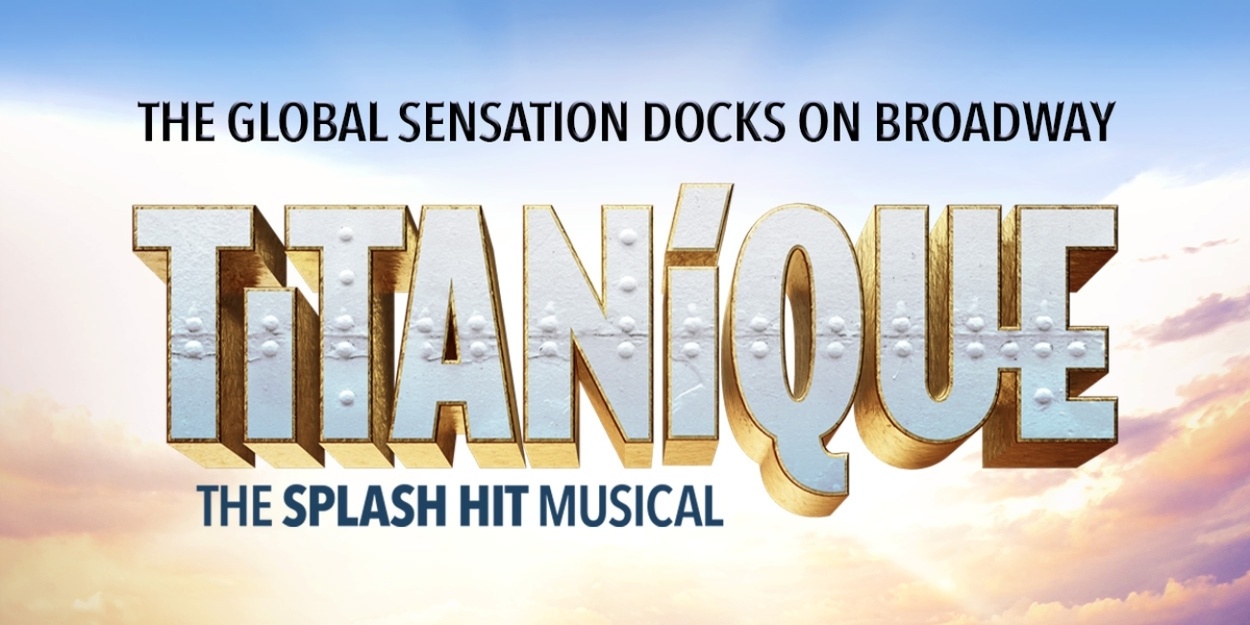

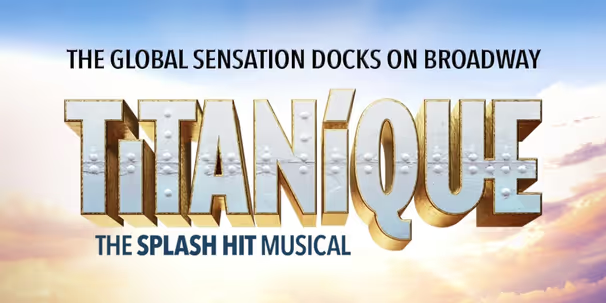

Contest: Win Opening Night Tickets to TITANIQUE on Broadway

The prize includes opening night tickets, dinner for two, and a merch prize pack.

Broadway Grosses: Week Ending 12/21/25 - MAMMA MIA! Plays its Best Week Ever on Broadway

View the latest Broadway Grosses

What Are American Theatre’s Most Influential Titles?

A recent survey ranks the most influential theatre titles of the last 25 years.

Twelve Days of Christmas: June Squibb

On the eleventh day of Christmas... life is wonderful.

Ticket Central

Industry

West End

Review: BEAUTY AND THE BEAST, New Wolsey Theatre

Beauty and the Beast runs at the New Wolsey Theatre until 17 January

Beauty and the Beast runs at the New Wolsey Theatre until 17 January

New York City

Interview: Director Shuler Hensley on Lush OKLAHOMA! Concert at Carnegie Hall

The 1/12 concert kicks of the Orchestra of St. Luke's 2026 season, which celebrates American music in honor of the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration

The 1/12 concert kicks of the Orchestra of St. Luke's 2026 season, which celebrates American music in honor of the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration

United States

Annex Theatre Announces Its 2026 Season: Season 39 — The Writing Is On The Wall

Seattle company enters its 39th season with new leadership and original work.

Seattle company enters its 39th season with new leadership and original work.

International

Final Premium Tickets Available for New Year's Eve Celebration at Sydney Opera House

Guests can choose between Puccini’s tragically beautiful, Madama Butterfly in the Joan Sutherland Theatre or the extravagant Opera Gala in the Concert Hall.

Guests can choose between Puccini’s tragically beautiful, Madama Butterfly in the Joan Sutherland Theatre or the extravagant Opera Gala in the Concert Hall.

.jpg)

.jpg?format=auto&width=606)