Trending Stories

Recommended for You

Contest: Win Opening Night Tickets to TITANIQUE on Broadway

The prize includes opening night tickets, dinner for two, and a merch prize pack.

BEETLEJUICE Will Host Sing-Along Finale at Closing Performance

The show will end its limited 13-week Broadway return engagement at The Palace Theatre on January 3, 2026.

20 Theater Books for Your Winter 2026 Reading List

Broadway authors this season include Liza Minnelli, John Doyle, Marc Shaiman, and more.

Broadway Grosses: Week Ending 12/28/25 - WICKED Reclaims Top Spot During Holidays

View the latest Broadway Grosses

Ticket Central

Industry

West End

Critics’ Choice: Franco Milazzo's Best Theatre Of 2025

"It’s difficult to say at which exact point I noticed that my jaw had dropped and stayed dropped."

"It’s difficult to say at which exact point I noticed that my jaw had dropped and stayed dropped."

New York City

Review: THANK YOU, TOM LEHRER at City Winery

A journey through the music & life of Mr. Tom Lehrer. The show returns on 2/16

A journey through the music & life of Mr. Tom Lehrer. The show returns on 2/16

United States

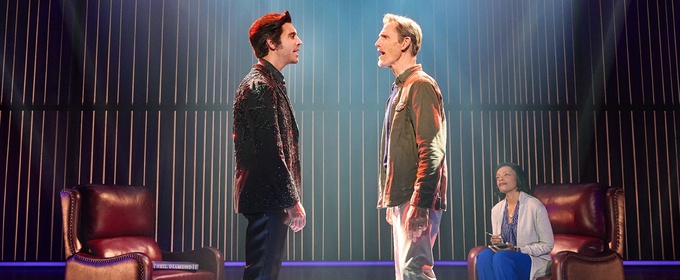

Review: THE NEIL DIAMOND MUSICAL A BEAUTIFUL NOISE at Broadway San Jose

Now through January 4th at Broadway San Jose!

Now through January 4th at Broadway San Jose!

International

Post-apokalyptický zážitek v podobě plzeňského JESUS CHRIST SUPERSTAR

Divadlo Josefa Kajetána Tyla uvedlo za dva roky uvádění již vice než šedesát repríz legendárního muzikálu

Divadlo Josefa Kajetána Tyla uvedlo za dva roky uvádění již vice než šedesát repríz legendárního muzikálu

.jpg)

.jpg?format=auto&width=606)